EXERCISES FOR RANGE

OF MOTION AND STRENGTHENING OF SHOULDER

The rehabilitation exercises shown in

this section are applicable to both nonoperative and postoperative treatment

for all of the shoulder conditions discussed in this book. The specific

exercises used, their progression, and their coordination with other treatment

modalities are specific to the diagnosis, the severity of the pathologic

process, and many other patient and surgical factors. A detailed discussion for

each of these conditions is beyond the scope of this book.

In general principles, the exercise

program should start with the easiest exercises to perform and can be

progressed when the early phase exercises can be done easily and with comfort.

The first priority in rehabilitation of the shoulder is pain management and to

avoid injury during the exercises. Pain management may include one or more of

the following: application of ice or heat; use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

agents, narcotic medication, corticosteroid injections, or bracing; nerve

blocks; or surgery. The first priority is to regain most of the passive range

of motion before concentrating on strengthening. Strengthening should include

both the shoulder and scapula as well as the trunk musculature. Strengthening

of the scapula should begin at the time to start phase I strengthening of the

glenohumeral musculature. Scapula-strengthening exercises include shoulder

shrugs and rowing-type exercises (shoulder protraction and retraction).

Coordination of scapula strengthening with glenohumeral strengthening is

necessary for successful progression to the overhead exercises of phase II. In

general, the progression of strengthening of the glenohumeral muscles should be

first strengthening the rotator cuff in nonimpingement arcs of motion (phase I)

to obtain good strength in rotation by the side as well as good scapula

strength before beginning active elevation strengthening. Before starting

resisted elevation with weights the patient should have full active elevation

without a weight. If this is not achieved, continue phase I strengthening and

scapula strengthening and add gatching and closed-chain active elevation

strengthening. When full active elevation is achieved without resistance, then

the patient can start phase II strengthening.

Most effective rehabilitation programs

require a daily home-based effort by

the patient. In most circumstances

the exercises should spread out over the day and not be concentrated into an

intense once-a-day regimen.

This basic principle of early shoulder

rehabilitation is particularly important in the early or acute stages of

rehabilitation when the shoulder is at its worst with respect to pain, motion,

or strength. The worse the problems, the more frequent the exercises should be

performed, but with short periods of exercise done well within the patient’s

abilities. The initial program should focus on the most key and deficient

problems for that diagnosis.

For example, the primary problem with early severe frozen shoulder is pain and

loss of passive range of motion. This should result in the need to achieve

effective pharmacologic pain management and to focus on passive range-of-motion

exercises to achieve improvements in passive range of motion and improvement in

pain before considering adding strengthening exercises to the program. The more

painful the shoulder, the more gentle the exercises, which are done for a

shorter duration but frequently during the day. As the shoulder improves, the

exercise periods can be more consolidated for longer duration and then

progressed with respect to intensity.

Patient education and participation is

critical to success for either nonoperative rehabilitation or post-operative

rehabilitation. Clear and precise communication between the physician and

patient and therapist is as important to a successful outcome as is the

precision and expertise by which all of the other treatment is performed,

including surgery.

Pendulum exercises are performed with

the patient leaning forward with the arm supported on a stable structure such

as a table and the waist bent at approximately 90 degrees. The affected

extremity is allowed to dangle in front of the patient’s body, and small

circular motions are made either clockwise or counterclockwise, allowing for

general passive range of motion of the glenohumeral joint.

Supine passive forward elevation is

done in the supine position using the unaffected extremity as a means to move

the affected arm passively or with active-assisted elevation (some muscle

activity of the affected shoulder). This is generally done in the plane of the

scapula. The plane of the scapula is midway between the true coronal plane

(parallel to the plane of the body [pure abduction] and the sagittal plane,

which is perpendicular to the plane of the body [pure forward flexion]). The

plane of the scapula lies 30 to 40 degrees anterior to the coronal plane. The

plane of the scapula for motion exercises places the rotator cuff and other

muscles of the shoulder in the most physiologic and natural position with

respect to the scapula body. For all passive exercises, when the arm reaches

its maximum level of gentle passive arc, there is a gentle stretch given to

increase the arc of motion. Repetitive movements are done during one session a

few times each day.

Active-assisted forward flexion can

also be done using an assistive device such as an exercise wand in the standing

position. Passive external rotation is done using a device such as a cane or

exercise wand. Cross-body adduction stretches the posterior capsule, and normal

posterior capsule length is important to achieve full forward elevation or full

internal rotation.

Basic Shoulder-Strengthening

Exercises

Progressive resistant strengthening exercises

can be performed in phases. Phase I involves the use of an elastic band for

external rotation with the arm by its side to avoid impingement or

overstressing of the rotator cuff tendons. The concept of progression of

strengthening from phase I to phase II is to first strengthen the rotator cuff

by doing rotational exercises in the least difficult or pain-provocative arm

and body position. After achievement of better rotator cuff strength and

shoulder function with the phase I exercises performed with the arm by the

side, then the shoulder should be better able to tolerate the more difficult

exercises for phase II strengthening.

Phase I strengthening can be done

either using both hands with the elastic band or with the elastic band to a

stationary object such as a doorknob with a pillow under the arm to provide

slight abduction and then external rotation away from the body. It is best to

use a stationary object so that the better or stronger shoulder does not

overpower the weaker shoulder. Internal rotation can likewise be performed with

the arm in slight abduction and internal rotation toward the abdomen. Extension

is performed in a similar matter with the elbow by the side pulling the band.

Forward flexion is shown with the elastic band with the arm moving in the

forward position generally below shoulder level. Many of these same exercises

can be performed with alternative techniques using a handheld 1- to 5-lb

weight.

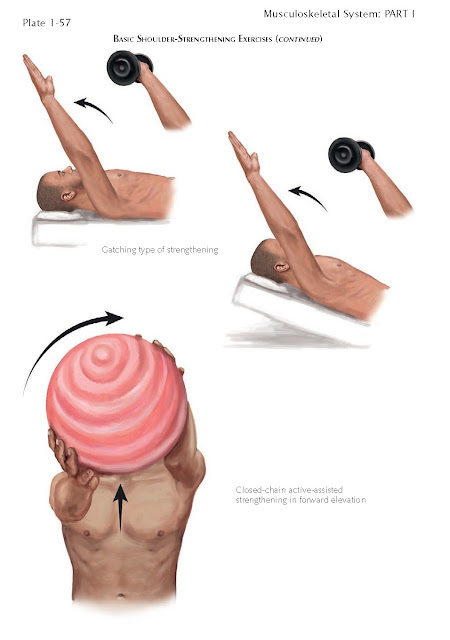

For patients with severe weakness of

forward elevation, graduated exercises are performed starting initially in the

supine position without a weighted extremity. The arm is actively elevated with

the patient in the supine position.

When this can be easily achieved with

multiple repetitions, a small 1-to 2-lb handheld weight is utilized again until

this can be done easily and repetitively. When this is accomplished, the

patient is then elevated with the torso at 30 to 40 degrees without a weighted

extremity. This is again tested repetitively until this can be done with ease,

after which a small 1-to 2-lb hand-held weight is added. This is repetitively

accomplished until the patient is able to g adually bring the arm up actively

in a seated position.

An alternative way to graduate to the

full active elevation without assistance is the use of closed-chain

activeassistance strengthening in forward flexion. This can be done with an

exercise wand or preferably by a lightweight exercise ball. The patient places

both arms on the ball and with assistance squeezes the ball and raises the arm

above the head. The weak side is on the upper portion of the ball and is

assisted by the strong arm, which is on the lower part of the ball. As the weak

shoulder becomes stronger, the patient moves his or her hands to an equal and

opposite side of the ball and when very strong can use the affected arm on the

underside of the ball as an assistant to the normal side. These exercises are

useful as an intermediate step to achieve full active elevation and progressive

resistive exercises and forward flexion above shoulder level.