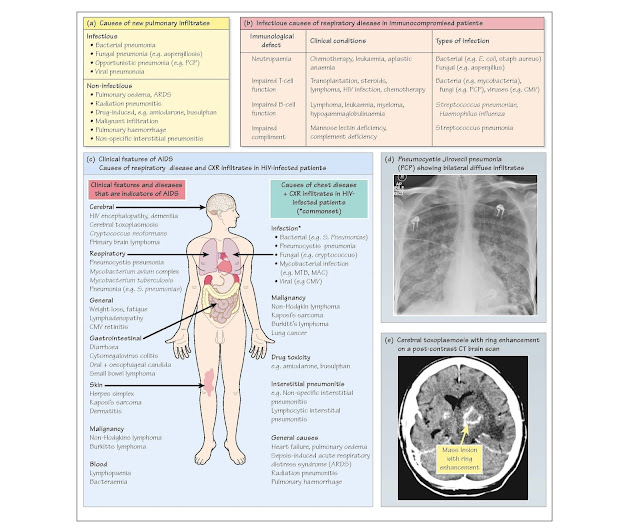

The Immunocompromised

Host

The immune system is most frequently impaired after chemotherapy and in

patients with human immunodeficien y virus (HIV) infection. Immunodeficien y

also occurs in patients with malignancies of the lym- phoproliferative system

(e.g. leukaemia), immediately following bone marrow transplants (BMT) and in

those on immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. steroids and azothioprine) particularly

after transplant surgery (e.g. renal). Malnutrition or chronic illness (e.g.

diabetes) may also impair immunity. Respiratory disease is particularly common

in the immunocompromised host.

Clinical presentation is often non-specifi (i.e. fever, dyspnoea, hy-

poxia, cough and chest discomfort) and investigation inconclusive making

diagnosis diff cult. In particular, pulmonary infiltrate are not always due to

infection (Fig. 39a). Clinical clues include rate of onset (i.e. rapid in

bacterial infection and slow with malignancy), drug therapy (e.g. methotrexate)

and extrapulmonary features (e.g. Kaposi's sarcoma). Establishing the diagnosis

may require invasive techniques (e.g. biopsy) with associated risks (e.g.

haemorrhage).

Investigations include blood and pleural fluid microscopy,

culture and serology. Sputum for Aspergillus or mycobacteria and

'induced' sputum for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumoniae (PCP). CXR f

ndings may be non-specifi (e.g. diffuse infiltrates) Chest CT scans assess ex-

tent of lung involvement, aid invasive sampling and may be diagnostic (e.g.

halo sign of aspergillosis). Consider early bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) with

microbiology, stains (e.g. fungus and virus), immunofluo rescence (e.g. PCP)

and serology (e.g. CMV and Cryptococcus) as this is often diagnostic

(50-60%). Transbronchial, f ne-needle and surgical lung biopsies have risks but

may aid diagnosis.

Diagnosis is due to respiratory infection in more than 75%

of cases:

· Infection depends on the immunological defect (Fig. 39b) and

prophylactic therapy (e.g. septrin for PCP).

· Non-infectious

causes present with similar

clinical and CXR features to infection and include pulmonary oedema, ARDS, malignancy

(e.g. lymphoma), diffuse alveolar haemorrhage, pulmonary embolism, drug-induced

disease (e.g. methotrexate), BMT-associated idiopathic pneumonia, radiation

pneumonitis and chronic graft-versus-host disease. More than one cause is often

present (30%).

Treatment is often empirical as antibiotic therapy cannot be

delayed in febrile neutropaenic patients, in whom infection is a medical

emergency. Blood cultures should always precede antibiotics.

· Antibiotic

choice depends on the clinical situation

and local antibiotic policy. Initial treatment of immunosuppressed cases

involves broad-spectrum antibiotics ( antiviral and antifungal agents).

Treatment should be adjusted when results are available. PCP and CMV therapy

have significan toxic side effects, but if suspicion is high, treatment is

started empirically. PCP can be diagnosed for up to 2 weeks after onset of

therapy. Treatment of mycobacteria is only started after definit ve diagnosis.

· Steroid

therapy is recommended in PCP,

radiation/drug-induced pneumonitis, BMT idiopathic pneumonia and alveolar

haemorrhage.

· Supportive

therapy includes supplemental

oxygen and ventilatory support. Respiratory failure has a poor outcome in these

patients.

Respiratory manifestations in the HIV-positive patient

(Fig. 39c)

Acquired immune deficien y syndrome

(AIDS) is due to infection with HIV, which impairs and depletes CD4

T-lymphocytes (Chapter 18). Reduction in T-lymphocyte availability predisposes

to viral or fungal infections and neoplasia (Fig. 39e). Highly active

antiretroviral therapy (HAART) allows T-lymphocyte population recovery, reduces

suscepti- bility to infection and improves survival. Nevertheless, HIV patients

are at increased risk of infection with common bacteria, PCP, mycobacteria and

fungi. Factors determining the type and risk of infection include the use of

prophylactic antibiotics (e.g. PCP prophylaxis), source of infection (e.g. TB

is more common with drug abuse) and geography (e.g. histoplasmosis and

coccidioidomycosis are more common in the USA). Extrapulmonary features (e.g.

Kaposi's sarcoma) may suggest the cause of pulmonary disease.

1. Infectious causes

· Bacterial pneumonia (e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus

aureus and Nocardia) is the commonest chest infection in HIV

patients. Rapid onset of high fever, purulent sputum and pleuritic chest pain

help distinguish bacterial pneumonia from PCP. Legionella infections are

more common in HIV patients.

· Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia occurs in severely immunocompromised patients (CD4 <200 106/L).

It has been less common since the use of septrin prophylaxis in high-risk

cases. It presents with gradual onset of fever, dry cough, exertional dyspnoea,

chest tightness, tachypnoea and rarely pneumothorax. Exercise-induced

desaturation progresses to resting hypoxaemia. CXR shows bilateral alveolar

infiltrate (Fig. 39d) but may be normal (10%) or show focal consolidation.

Diagnosis requires detection of pneumocysts in induced sputum ( ̴60-70%) or BAL (>90%). High-dose

co-trimoxazole is the most effective therapy but may cause rashes ( ̴30%), vomiting and blood disorders. Pentamidine

and dapsone are second-line alternatives. High-dose steroids reduce alveolitis,

respiratory failure and mortality.

· Mycobacteria (e.g. Mycobacterium tuberculosis

(MTB), My- cobacterium avium complex (MAC)). Globally 10% of

MTB cases are also infected with HIV. However, co-infection rates vary

geographically affecting 35-40% in sub-Saharan cases and 2.7% in the UK. HIV

patients with previous MTB exposure have a 10% chance of reactivation, and

approximately 33% of patients exposed to MTB develop primary disease. Advanced

immunosuppression is typically associated with diffuse pulmonary involvement,

mediastinal adenopathy and extrapulmonary involvement. Symptoms may deteriorate

with the onset of HAART due to immune reconstitution. Non-tuberculous

mycobacterial (NTM) infection is due to MAC in more than 90% of cases. MAC

treatment is lifelong unless immune restoration is achieved with HARRT.

· Viral (e.g. influenz and herpes simplex). Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is

ubiquitous and normally harmless but can cause life-threatening pneumonia in

the immunocompromised. Diagnosis requires evidence of viraemia (i.e.

antigen/PCR testing on blood/BAL) or tissue invasion (e.g. 'owl eye' inclusion

bodies in infected biopsy cells). Ganciclovir is the most effective antiviral

agent.

· Fungal (e.g. Aspergillus). Cryptococcus neoformans propagates

asymptomatically in alveoli following inhalation (from bird drop-pings), before

migrating to the CNS where it causes meningitis ( ± encephalitis). Onset is acute

or chronic with fever, cough and non-specifi CXR changes. The cryptococcal

antigen test and India ink stain establish the diagnosis. Treatment is with

amphotericin, fluytosine and fuconazole. In endemic areas, histoplasmosis and

coccidioidomycosis may cause respiratory disease.

2. Non-infectious causes

· Malignancies are occasionally confused with infection in HIV patients. Kaposi’s

sarcoma is a tumour of vascular origin associated with human herpesvirus 8

infection. Clinical manifestations range from asymptomatic incidental discovery

to fulminating disease, causing respiratory failure. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma occurs

in advanced immunosuppression and is typically aggressive B-cell or Burkitt's

lymphoma, suggesting pre-existing herpesvirus infection. Lung cancer is

also increased in HIV patients.

· Interstitial pneumonitis (e.g. NSIP, LIP, Chapter 30).

· Drug-induced lung disease or heart failur