Anomalies In Number Of Kidneys

Renal agenesis is defined as the complete absence of one

or both pairs of kidneys and ureters. It represents a failure of the ureteric

bud and metanephric mesenchyme to engage in the process of reciprocal induction

and differentiation required for metanephros formation. As a result, both the

kidney and ureter fail to develop. Renal aplasia, in contrast, occurs when

there is abnormal differentiation of the metanephric mesenchyme and ureteric bud

that leads to involution of the kidney, but with persistence of a rudimentary

collecting system.

Because numerous signaling molecules are involved in

normal metanephros development, the range of genetic defects that may cause

renal agenesis is vast and under active investigation. Recent evidence,

however, suggests a prominent role for abnormalities in the GDNF-RET signaling

cascade. GDNF (glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor) is expressed in the

masses of metanephric mesenchyme lying near the mesonephric (wolffian) ducts. It

binds to RET, a receptor tyrosine kinase, in the mesonephric ducts and induces

formation of the ureteric buds. Mutations in the genes encoding these proteins

prevent formation of the ureteric buds and have been noted in fetuses with

renal agenesis.

In some cases, male fetuses with renal agenesis still

develop normal mesonephric duct derivatives (i.e., the vas deferens, seminal

glands [vesicles], and epididymis), indicating that the underlying

developmental defect affected only ureteric bud branching or metanephric

induction. Fetuses with broader defects, in contrast, have likely sustained insults

to the intermediate mesoderm, which gives rise to both the nephrogenic cords

and genital ridge (see Plate 2-1).

Bilateral renal agenesis. Bilateral renal agenesis, defined as the complete absence of both

kidneys and ureters, is a rare abnormality that occurs in approximately 1 :

5000 to 1 : 10,000 fetuses. Males are affected at least twice as often as

females. There is evidence that a significant number of affected fetuses have

abnormalities in signaling cascades important to renal development, such as the

GDNF-RET pathway described above. A subset of affected fetuses, however, also

have associated abnormalities that suggest a more wideranging defect in caudal

development, such as sirenomelia (fused lower extremities, imperforate anus,

renal agenesis, and abnormal or absent genitalia).

Bilateral renal agenesis is typically diagnosed using

prenatal ultrasound. Normally the fetal kidneys can be visualized starting at

approximately the twelfth week of gestation. In bilateral renal agenesis,

however, no renal parenchyma can be visualized either in the normal renal fossae or

other ectopic locations, such as the fetal pelvis or thorax. The fetal adrenal

glands are in normal position but may appear less flattened because of the lack

of normal compression from the kidneys. Finally, the fetal bladder appears

empty, and the normal cycles of filling and emptying are not seen.

Severe oligohydramnios is a major consequence of

bilateral renal agenesis and may be one of the more notable sonographic

findings. Before 20 weeks of gestation, diffusion of fluid into the amnion

produces a significant

fraction of the amniotic fluid, which there-fore may appear normal in volume

even despite a lack of fetal renal function. After 20 weeks, however, the fetal

kidneys are responsible for producing over 90% of the amniotic fluid. Severe

oligohydramnios at this stage of development is therefore a very sensitive sign

of bilateral agenesis. It is not, however, particularly specific, and other

possible causes including bilateral renal dysplasia, bilateral renal cystic

disease, urinary outflow tract obstruction, premature rupture of membranes, and

fetal demise must be ruled out.

Severe oligohydramnios, irrespective of the cause, has

numerous adverse effects on the fetus. First, the increase in intrauterine

pressure results in physical compression of the growing fetus, which leads to a

blunted nose; low-set, flattened ears that appear enlarged; micrognathia;

prominent infraorbital folds; a prominent depression between the lower lip and

chin; clubbed limbs; and dislocated hips. In addition, the lack of amniotic

fluid causes abnormal development of the skin, which appears loose and

excessively dry. Finally, the increased pressure on the fetal thorax and

decline in circulating amniotic fluid leads to severe pulmonary hypoplasia. The

cause-and-effect relationship between oligohydramnios and these various

sequelae is known as the Potter sequence.

Bilateral renal agenesis is fatal. Forty percent of

affected fetuses die in utero, and the remainder develop severe respiratory

distress shortly after birth. There-fore, if the diagnosis is established using

prenatal ultra- sound, therapeutic abortion is typically recommended. Because

most cases of bilateral renal agenesis are sporadic, the risk of recurrence in

a subsequent pregnancy is low.

Unilateral renal agenesis. Unilateral renal agenesis, defined as the complete absence of one

kidney and its associated ureter, occurs in approximately 1 : 1000 to 1 : 1200

individuals. Males are affected nearly twice as often as females. The

underlying cause is thought to be abnormal interaction between a ureteric bud

and its associated metanephric mesenchyme; however, it is unclear why some

patients develop unilateral agenesis, whereas in others both sides are

affected.

Like bilateral agenesis, unilateral renal agenesis is

often discovered using prenatal ultrasound, which reveals an empty renal fossa

without evidence of ectopic renal parenchyma, such as a pelvic kidney. Unlike

in bilateral agenesis, however, urine production is normal, and therefore

oligohydramnios does not occur. As a result, affected infants are typically born with a

normal appearance and normal pulmonary function.

Many patients with unilateral renal agenesis have

associated abnormalities in other organ systems. Indeed, the absence of a

kidney may not even be discovered until an associated abnormality is

investigated. Many of these abnormalities occur in structures derived from the

mesonephric or paramesonephric ducts, suggesting a defect in the intermediate

mesoderm early in development. In males, the ipsilateral mesonephric duct derivatives

(vas deferens, seminal gland [vesicle], and epididymis) may be absent or

rudimentary (i.e., a seminal gland [vesicle] cyst). Meanwhile, in females, a

common associated anomaly is a unicornuate uterus, in which the side

ipsilateral to the absent kidney is missing. Associated abnormalities may also

occur in the cardiovascular system (e.g., septal or valvular defects) or

gastrointestinal systems (e.g., imperforate anus).

Nearby

musculoskeletal abnormalities may also be seen. In a smaller subset of

patients, unilateral renal agenesis may be associated with a genetic syndrome

that affects numerous organ systems, such as BOR (branchio-oto-renal) syndrome,

Turner syndrome, Fanconi anemia, Kallmann syndrome, VACTERL (vertebral

anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal

defects, limb defects), and others.

With a solitary kidney, renal function typically remains

normal, although for unclear reasons there is an increased risk of

vesicoureteral reflux, ureteropelvic junction obstruction, and ureterovesical

junction obstruction. Later in life, some patients may develop renal

insufficiency and proteinuria, likely secondary to hyperfiltration of the solitary

kidney causing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (see Plate 4-10). Their survival

rate, however, appears to remain similar to that of normal individuals.

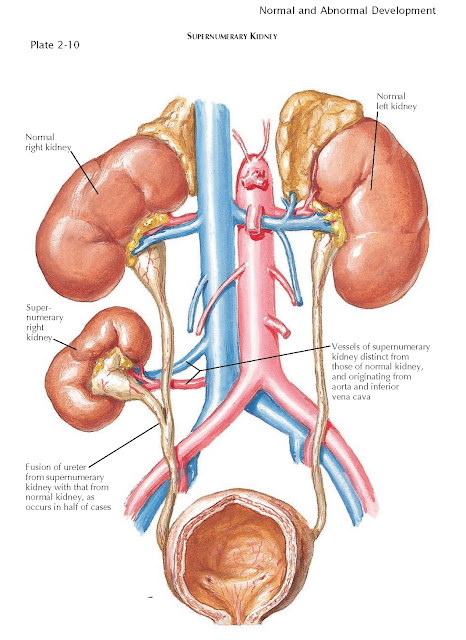

Supernumerary Kidney

A supernumerary kidney is a very rare congenital

anomaly. Unlike a kidney with a duplicated collecting system, which is far more

common, a supernumerary kidney is a distinct mass of renal parenchyma with its

own capsule, vessels, and collecting system. It is typically small and located

just cephalad or caudal to the normally positioned kidney on the same side.

Less commonly, it is located in a variety of other positions, such as the pelvis

or midline. In some cases, the supernumerary kidney and normally positioned

kidney may be loosely attached to each other by either fibrous tissue or a

bridge of renal parenchyma.

In half of cases, the ureter associated with a supernumerary

kidney fuses with that of the normally positioned ipsilateral kidney, as seen

in the illustration; in the other half, the ureter has its own separate

insertion into the bladder. In such cases, the Weigert-Meyer rule is usually

obeyed, meaning that the ureter associated with the more caudally positioned

kidney has an orifice located more superior and lateral than that of the cranially

positioned kidney. The vessels to the supernumerary kidney usually originate

from the aorta and inferior vena cava, although their origin is more variable

with more caudally positioned kidneys.

The embryologic basis of the supernumerary kidney is not

known but likely represents early division of the metanephric mesenchyme. A

supernumerary kidney with a ureter that has its own insertion into the bladder

likely reflects early division of the mesenchyme before insertion and branching

of the ureteric bud (see Plate 2-2). The ureter to the supernumerary kidney

probably represents a second ureteric bud that sprouted from the adjacent

mesonephric duct, either by coincidence or as a direct effect of the divided

mesenchyme. A supernumerary kidney with a ureter that fuses with that of the

normal kidney likely reflects later division of the meta-nephric mesenchyme,

perhaps in response to a ureteric bud that divided before insertion.

Supernumerary kidneys are often asymptomatic and do not

affect overall renal function. Thus a significant number of such kidneys

may never be discovered or may be noted only as incidental findings during the

workup of another unrelated complaint. In some patients, however, supernumerary

kidneys present as palpable abdominal masses or cause symptomatic nephrolithiasis

or an upper urinary tract infection. Because of the rarity of this condition,

affected patients are often not diagnosed until their fourth decade, if at

all.