Male Reproduction Pathophysiology

Clinical background

Male infertility has a large number of

causes, both endocrine and non-endocrine in origin and few are specifically

treatable. In the majority of cases an exact diagnosis is not reached despite

investigation and the condition may result from previous testicular damage,

varicocoele or non-specific inflammation. All patients should be assessed with

their partner in a specialist fertility unit and in the undiagnosed group the

use of intracytoplasmic sperm injection may offer the best chance of fertility.

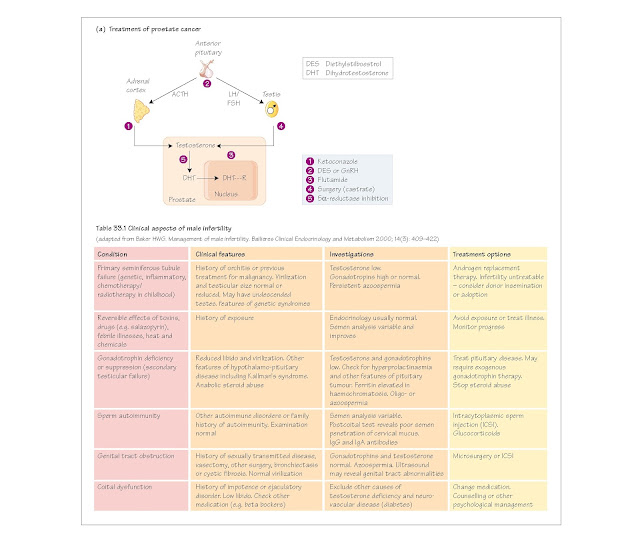

The clinical features of male infertility are shown in Table 33.1.

Male reproductive pathophysiology

Hypogonadism is the failure of

the testes to function, that is to produce testosterone and spermatozoa, and

can be due to genetic defects (see Chapter 23). Primary hypogonadism refers

to abnormalities within the gonad, for example Leydig cell agenesis

(non-development), or failure of Leydig cells in adult life. Leydig cell

failure can occur after mumps. Secondary hypogonadism refers to

gonadotrophin deficiency or failure to secrete gonadotrophin-releasing hormone

(GnRH), and is also called hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism.

Hypergonadism means the excess activity of the gonad, which can

be virilizing due to androgen-secreting Leydig cell tumours, or feminizing

due to estrogen-producing Leydig cell tumours. This is primary

hypergonadism, whereas that pro- duced through excess GnRH and/or

gonadotrophin production is secondary hypergonadism.

Androgen resistance is caused by mutations of the androgen receptor,

which no longer binds androgen with sufficient affinity for a normal androgenic

response to be maintained, or by the complete absence of the androgen receptor.

Gynaecomastia is breast enlargement in males. It usually occurs

through abnormal endogenous or exogenous estrogens. Gynaecomastia accompanied

by galactorrhoea (milk production) may be indicative of a prolactin-secreting

tumour. Gynaecomastia sometimes occurs in ageing men, which may be because of

an increasing estrogen/ androgen ratio in the blood. The condition has also

been reported after the smoking of cannabis, which is known to decrease

testosterone synthesis and to drive down libido.

Impotence (erectile dysfunction) is the failure to achieve

erection of the penis, and has numerous vascular and neurologi- cal causes,

although few of endocrine origin. Erection is caused by nerve impulses passing

through parasympathetic efferents, the nervi erigentes, to the penis. The

result is vasodilatation of penile arteries, which allows the build-up of

arterial blood in the corpus cavernosum and the corpus spongiosum.

The treatment of impotence was

revolutionized by the introduction of sildenafil (Viagra). The drug dilates

penile blood vessels by blocking the enzyme phosphodiesterase-5, which normally

metabolizes the second messenger cyclic GMP, which in turn is permitted to

prolong vascular smooth muscle relaxation in the penis, which is thus engorged

with blood.

Prostatic pathophysiology

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the growth of the medial lobe of the human

prostate, most often in late middleaged men, until it presses on and begins to

occlude the urethra. It is termed ‘benign’ because it does not invade other

tissues and destroy them, or metastasize to distant sites in the body. BPH is

androgen-dependent, being strongly stimulated by dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the

active androgenic metabolite of testosterone in the prostate gland. The most

effective treatment has been the surgical removal of all or part of the gland.

The operation can be performed through the bladder (transvesical prostatectomy)

or through the urethra (transurethral resection), when prostate tissue is

burned away using a heated element. Recently, inhibitors of the enzyme

5α-reductase, which converts testosterone to DHT, have been introduced to treat

BPH.

Prostate cancer. Carcinoma of the prostate is virtually always

androgen-dependent. Various approaches to treatment are shown in Fig. 33a. The

aim is to remove the tumour and all sources of androgen production. Medical

treatment may involve the administration of stable analogues of GnRH, such as buserelin.

These, if continuously present in the bloodstream, down regulate anterior

pituitary production of gonadotrophins by rendering the gonadotrophs

insensitive to GnRH from the hypothalamus. The result is a chemical castration,

which can be reversed by stopping treatment. Another approach is the

administration of androgen receptor blockers such as flutamide, finasteride

or cyproterone acetate.

When using GnRH analogues, it is

advisable when starting treatment to administer the drug together with an

antiandrogen. This is because the initial effect of the GnRH analogue is to

stimulate a transient increase in testosterone production, which may in turn

cause stimulation of tumour activity. Radiotherapy may be necessary as an

adjunctive therapy or for the relief of pain due to metastatic spread.