Assessment For Kidney Transplantion

Although renal transplantation improves both quality of life and survival,

it involves a significant investment of health resources and the use of an

organ with a limited supply. It is therefore of utmost importance that the

potential transplant recipient is carefully assessed, both to avoid unnecessary

exposure to the risks of a general anaesthetic and to ensure appropriate use of

a precious resource. To this end, every potential transplant recipient is assessed

by taking a careful history, performing a thorough examination and undertaking

a number of investigations.

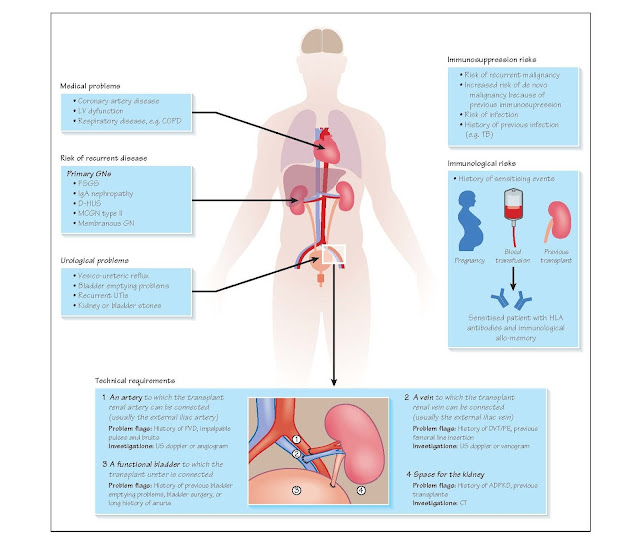

The transplant work-up must answer five questions.

1 Does the patient have any medical problems which put

them at risk of operative morbidity/mortality? Patients with CKD are at increased risk of coronary, cerebral and

peripheral vascular disease, and should be assessed for a past or current

history of cardiac problems (e.g. angina, myocardial infarction, rheumatic

fever), strokes or peripheral vascular disease (claudication/amputation). Risk

factors assessed include family history, smoking history and a history of

diabetes mellitus or hypercholesterolaemia. Smoking is also associated with the

development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A good screening

question to assess general cardiorespiratory fitness is to ask how far the

patient can walk; a good test is to make them walk.

Dialysis patients are frequently oligo-anuric and often

struggle to restrict their fluid intake. This leads to chronic volume overload

and hypertension, resulting in left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) or

dysfunction. Patient who require 3–4 litres of fluid to be removed at each

dialysis session frequently develop such cardiac problems.

CKD is also associated with tertiary hyperparathyroidism

and hypercalcaemia, which increases the risk of vascular and valvular

calcification, particularly the aortic valve.

Examination should pay particular attention to

cardiovascular signs: pulse rhythm and volume, signs of volume overload (ele-

vated jugular venous pressure [JVP], peripheral and pulmonary oedema), signs of

LVH (hyperdynamic apex beat) or LV dilatation (displaced apex beat) and signs

of valvular heart disease (particularly the ejection systolic murmur of calcific

aortic stenosis). The chest should be assessed for signs of COPD

(hyperinflation, reduced expansion, wheeze) or for pleural effusions which may

occur in patients on peritoneal dialysis.

Cardiorespiratory investigations include an

electrocardiogram (ECG), a chest radiograph, a cardiac stress test (an exercise

tolerance test or an isotope perfusion study) and an echocardiogram (to assess

LV function). If these are abnormal, then the patient may need further

cardiological assessment, including coronary angiography.

2. Does the patient have any conditions that make them

technically difficult to transplant?

There are four basic technical requirements for

implantation of a kidney.

· An artery (usually the external

iliac artery), to which the trans- plant renal artery will be anastomosed.

Severe vascular disease can make the arterial anastomosis difficult, therefore

all of the patient’s lower limb pulses should be carefully assessed during

examination, including auscultation of the femoral arteries and aortic bifurca-

tion for bruits, as a surrogate for iliac artery disease. Duplex imaging is

indicated if any abnormality is detected or suspected.

· A vein (usually the external iliac vein), to which

the transplant renal vein will be anastomosed. A history of venous thromboem-

bolic disease, particularly clots in the lower limb veins, should be sought; a

transplant should not be placed above a limb where a thrombosis has occurred

previously. Patients on chronic haemo- dialysis may have had numerous lines

inserted into their femoral veins, which can lead to stenosis and thrombosis.

Look for col- laterals, cutaneous signs of venous hypertension and oedema,

which may be associated with venous compromise. Duplex imaging or percutaneous

venography may be required.

· A bladder, to which the transplant

ureter will be anastomosed. A history of urological problems, including

congenital bladder malformations or reflux, is of relevance. If these issues

are not resolved prior to transplantation, then they may recur and damage the

transplanted kidney. Patients who have had ESRF for a number of years often

have negligible urine output and a small, shrunken bladder, which is difficult

to find intra-operatively and will only hold small volumes of urine post

transplant. Some patients need a neobladder fashioned from a segment of their

ileum (a urostomy).

· Space for the kidney. Some

patients with polycystic kidney disease have grossly enlarged native

kidneys that extend into the lower abdomen and may require removal prior to

transplantation. In addition, patients with an elevated body mass index (BMI)

may be technically difficult to transplant, due to lack of space for the graft

and reduced ease of access to the vessels. Therefore, most centres will not

list patients for transplantation unless the BMI is <35 kg/m2.

3. Is the patient at increased risk of the immunological complications of

transplantation?

The immune system remains a significant barrier to

transplantation in patients with pre-formed antibodies to non-self human

leucocyte antigens (HLA). This usually occurs as a result of a sensitising

event, for example blood transfusion, pregnancy (particularly by multiple

partners), or previous renal transplants or other allografts (e.g. skin

grafts). The frequency of such events should be ascertained.

4. Is the patient at increased risk of immunosuppression-associated

complications?

Patients with ESRF secondary to a primary or secondary

glomerulonephritis (e.g. IgA, vasculitis or lupus) have frequently been treated

with immunosuppressants. This includes the use of toxic agents, such as

cyclophosphamide, or biological agents, including alemtuzumab or rituximab.

Heavy immunosuppression should be avoided in such patients post-transplant,

particularly the use of lymphocyte-depleting agents such as anti-thymocyte

globulin (ATG), which may place them at high risk of infectious complications.

Immunosuppression also increases the risk of developing a

de novo cancer (particularly oncovirus-associated malignancies), and

enhances the progression of existing cancers. Thus, most centres would agree

that patients with a history of malignancy must be cancer-free for at least 5

years prior to transplantation.

5. Is the patient at risk of recurrent disease in their transplant?

Some pathologies that cause CKD can recur in the

transplant and reduce its long-term function and survival. A number of

glomerulonephritides can affect the graft (e.g. IgA nephropathy and focal

segmental glomerulosclerosis [FSGS]). In the case of FSGS, the patient may

develop recurrent disease immediately post transplant (usually evidenced by

heavy proteinuria). This is sometimes amenable to treatment with plasma

exchange, therefore it is important to recognise this risk and carefully

monitor the patient post transplant. If a patient has developed rapidly

progressive, recurrent disease in a transplant kidney, then this is a relative

contraindication to re-transplantation.