Masseter, Temporalis and Infratemporal Fossa

Masseter

(Fig. 7.29) attaches along the length of the

zygomatic arch and its fibres slope downwards and backwards to the lateral

surface of the ramus of the mandible adjacent to the angle (Fig. 7.31). This

muscle is a powerful elevator of the mandible

and is easily palpated when the teeth are clenched. It is supplied by the

masseteric branch of the mandibular (V3) division of the trigeminal nerve.

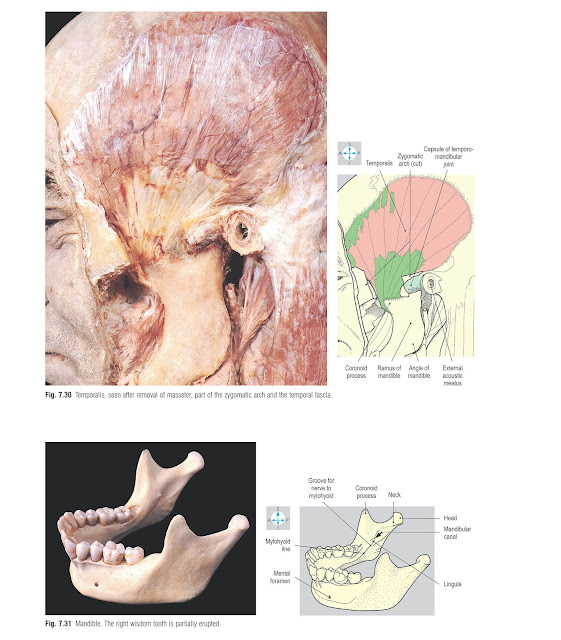

Temporalis

Temporalis

(Fig. 7.30) is a large fan-shaped muscle occupying the temporal fossa and

taking attachment from the area of bone bounded by the inferior temporal line.

The more superficial fibres arise from the temporal fascia that covers the

muscle and is attached to the superior temporal line. All the fibres descend

deep to the zygomatic arch to attach to the coronoid process and anteromedial

aspect of the ramus of the mandible (Fig. 7.31). Temporalis elevates the

mandible, as in closing the mouth, and its posterior fibres retract the

mandible. The deep temporal branches of the mandibular (V3) division of the

trigeminal nerve supply the muscle from its deep surface.

Infratemporal

fossa

This

fossa lies deep to the ramus of the mandible and is limited on its medial

aspect by the lateral wall of the pharynx and the medial pterygoid plate of the

sphenoid bone. The fossa is bounded by the posterior surface of the maxilla in

front and by the styloid process and its attached muscles behind. The roof is

provided by the temporal and sphenoid bones in the base of the skull while

inferiorly the fossa is continuous with the neck.

Within

the fossa are the two pterygoid muscles, the mandibular (V3) division of the

trigeminal nerve and its branches, and the maxillary vessels and their

branches. Adjacent to the fossa is the temporomandibular joint.

Pterygoid

muscles

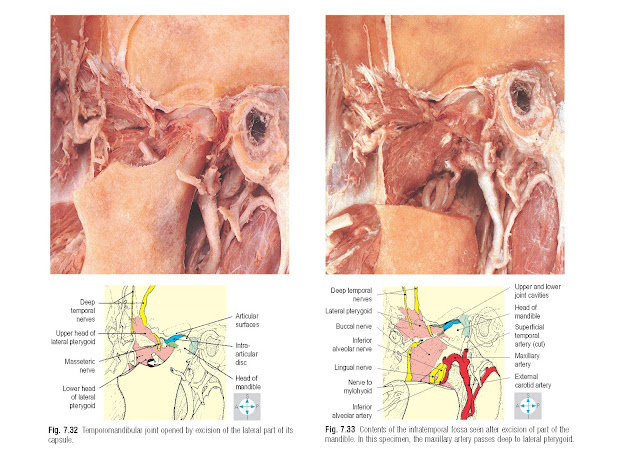

Each

of the lateral and medial pterygoid muscles (Figs 7.32–7.34) has two

attachments to the skull. The upper head of the lateral pterygoid attaches to

the inferior surface of the greater wing of the sphenoid. The lower head

attaches to the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid plate. Both heads

converge on the neck of the mandible and the capsule of the temporomandibular

joint. The lateral pterygoid pulls forward both the neck of the mandible and

the articular disc, thus depressing the mandible and opening the mouth.

The

lower head of the lateral pterygoid is clasped by the two heads of the medial

pterygoid. The deep head of the latter is larger and attaches to the medial

surface of the lateral pterygoid plate. The superficial head is attached to the

tuberosity of the maxilla. The fibres of both heads incline obliquely

downwards, backwards and laterally to attach to the medial surface of the angle

of the mandible. The muscle is a powerful elevator of the mandible.

The

temporomandibular joint (Fig. 7.32) is a

synovial joint. The head of the mandible articulates with the articular fossa

and eminence of the temporal bone. Fibrocartilage covers the articular surfaces

and also forms an articular disc, which divides the joint into two separate

cavities. Within these cavities, the non-cartilaginous surfaces are lined with

synovial membrane.

The

fibrous capsule surrounding the joint is attached to the margin of the

articular cartilage and to the neck of the mandible. Anteriorly, it receives

the attachment of the lateral pterygoid while its deep surface is firmly

adherent to the periphery of the articular disc.

Laterally,

the capsule (Fig. 7.30) is thickened to form the lateral ligament, which

inclines posteroinferiorly from the root of the zygomatic arch to the neck of

the mandible. Two accessory ligaments lie medial to the joint, although not in

contact with the capsule. The sphenomandibular ligament extends from the spine

of the sphenoid to the lingula adjacent to the mandibular foramen. The

stylomandibular ligament, a thickening of the parotid fascia, passes from the

styloid process to the angle of the mandible.

The

joint receives its nerve supply from the auriculotemporal and masseteric

branches of the mandibular (V3) division of the trigeminal nerve.

Movements

at the joint include elevation, depression, protraction and retraction of the

mandible. The head of the mandible does not merely rotate in the articular

fossa but also moves forwards onto the articular eminence of the temporal bone,

taking the articular disc with it. The alternate protraction and retraction of

right and left sides produces the grinding movements used in chewing. The

muscles responsible for these movements are known collectively as the muscles

of mastication. The mouth is closed by contraction of masseter, temporalis and

medial pterygoid. The lateral pterygoid protracts the mandible and, assisted by

digastric and mylohyoid (p. 348), also opens the mouth. Retraction is produced

by the posterior fibres of temporalis. When the mandible is fully depressed,

the joint is relatively unstable and dislocation may occur, the head of the

mandible moving in front of the articular eminence and resulting in an

inability to close the mouth.

The

mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (Figs 7.33 & 7.34) contains

sensory and motor fibres and enters the infratemporal fossa through the foramen

ovale in the sphenoid. Two small branches arise from the short main trunk of

the nerve. The first branch ascends through the foramen spinosum to receive

sensation from the meninges of the middle cranial fossa. The other branch is

motor, supplying the medial pterygoid and giving a small branch that passes

through the otic ganglion (lying just medial to the main trunk of the

mandibular division) to supply tensor tympani and tensor veli palatini.

The

main trunk descends between the lateral pterygoid and tensor veli palatini

muscles, dividing into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior division

is mainly motor and gives masseteric, deep temporal, lateral pterygoid and

buccal branches. The masseteric nerve (Fig. 7.32) curves laterally above the

lateral pterygoid to enter the deep surface of masseter. Two or three deep

temporal nerves (Fig. 7.33) ascend deep to temporalis, which they supply, and

further branches enter the deep surface of the lateral pterygoid. The buccal nerve

(Figs 7.33 & 7.34) is a sensory branch that passes forwards between the two

heads of the lateral pterygoid to supply the skin over the cheek and the mucosa

lining the cheek, which it reaches by piercing, but not supplying, buccinator.

The

posterior division of the main trunk is mainly sensory and has three branches,

the auriculotemporal, lingual and inferior alveolar nerves. The

auriculotemporal nerve (Fig. 7.34) arises

by two roots, which clasp the origin of the middle meningeal artery. The nerve

passes backwards before turning superiorly behind the temporomandibular joint

to ascend in company with the superfi- cial temporal vessels. It gives

secretomotor branches to the parotid gland (p. 339) and conveys sensation from

the temporal region, the upper half of the pinna and most of the external

acoustic meatus.

The

lingual nerve (Figs 7.33 & 7.34) inclines downwards and forwards between

the pterygoids, deviating medially to pass below the superior constrictor of

the pharynx. In the floor of the mouth it runs forwards lateral to the

hyoglossus muscle, at whose anterior border it again turns medially to pass

inferior to the submandibular duct and enter the base of the tongue. It conveys

general sensation from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. Near the lower

border of the lateral pterygoid the lingual nerve is joined by the chorda

tympani (a branch of the facial nerve). Arising within the temporal bone, the

chorda tympani emerges from the petrotympanic fissure. It carries taste fibres,

which have travelled in the lingual nerve from the anterior two-thirds of the

tongue and preganglionic parasympathetic fibres destined for the submandibular

ganglion (p. 352).

The

inferior alveolar nerve (Figs 7.33 & 7.34) descends medial to the lateral

pterygoid and gives rise to a motor branch that curves downwards to supply

mylohyoid and the anterior belly of digastric. The inferior alveolar nerve then

enters the mandibular foramen in the ramus of the mandible and runs forwards in

the mandibular canal, supplying the lower teeth and alveolar ridge. Its mental

branch emerges from the mental foramen to supply skin overlying the chin. Local

anaesthetic injected near the inferior alveolar nerve as it enters the

mandibular foramen will block sensation from the lower teeth and gums on that

side of the mouth. Often there is loss of sensation in the same side of the

tongue because of the proximity of the lingual nerve

This

artery (Figs 7.33 & 7.34) arises in the parotid gland (p. 339) as a

terminal branch of the external carotid artery, passes antero- superiorly

across the infratemporal fossa, usually lateral to the lateral pterygoid, and traverses the

pterygomaxillary fissure to enter the pterygopalatine fossa where terminal branches

arise. These correspond to branches of the maxillary nerve (p. 353).

In

the infratemporal fossa, the maxillary artery gives branches to supply

masseter, temporalis and the pterygoid muscles. In addition, the middle

meningeal artery arises deep to the lateral pterygoid, embraced by the two

roots of the auriculotemporal nerve. It traverses the foramen spinosum and

within the cranium supplies the meninges of the middle cranial fossa and the

cranial vault.

The

maxillary artery also gives rise to the inferior alveolar artery, which

accompanies the nerve into the mandibular canal. Further small branches supply

the middle ear and the lining of the external acoustic meatus.

Maxillary artery

Veins

within the pterygopalatine fossa form a plexus that extends through the

pterygomaxillary fissure into the infratemporal fossa, where the plexus is

related to the pterygoid muscles. This pterygoid plexus has important

connections to the cavernous sinus in the skull and infraorbital and ophthalmic

veins. The plexus drains by the maxillary vein into the retromandibular vein

(p. 340).