Inguinal Canal Anatomy

The inguinal canal is

about 4 cm long and passes obliquely through the flat muscles of the abdominal

wall just above the medial half of the inguinal ligament (Fig.

4.19). In the male, the canal conveys the spermatic cord (comprising the

ductus [vas] deferens and the vessels and nerves of the testis). In the female,

the canal is narrower and contains the round ligament of the uterus.

The lateral end of the canal opens into the abdominal

cavity at the midinguinal point, defined as midway between the pubic symphysis

and the anterior superior iliac spine. In clinical practice, the midinguinal

point serves as a guide to the deep inguinal ring and the femoral artery (Fig.

4.2). There may be individual variation in the relative positions of the deep

inguinal ring, the femoral artery, and the bony landmarks, and some authors

refer to the midinguinal point or the midpoint of the inguinal ligament as

appropriate surface markings. The medial end of the canal opens into the

subcutaneous tissues at the superficial inguinal ring, an aperture in the

external oblique aponeurosis immediately superior to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 4.20). Continuous with the margins of the

superficial ring is a thin sleeve surrounding the spermatic cord, the external spermatic

fascia (Fig. 4.21).

The canal comprises a floor, a roof, and an anterior and

a posterior wall. The gutter-shaped floor is formed by the inguinal ligament (Fig. 4.22), the in-turned lower edge of the external

oblique aponeurosis. The ligament attaches laterally to the anterior superior

iliac spine and medially to the pubic tubercle and the pectineal line of the

pubis. The expanded medial end of the inguinal ligament, the lacunar ligament,

lies in the floor of the medial end of the canal, and its concave lateral edge

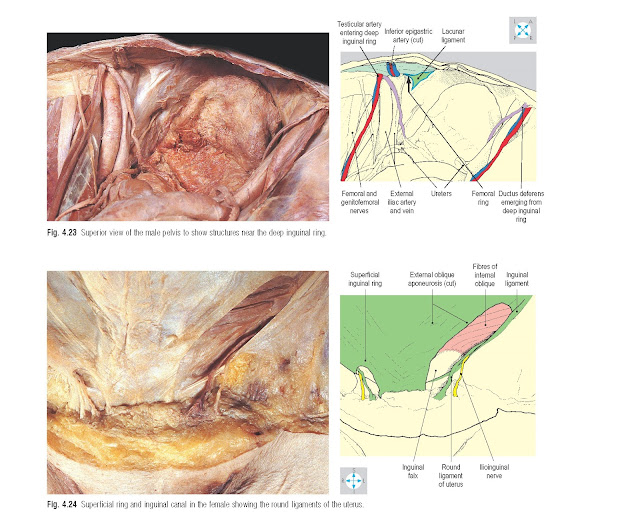

forms the medial boundary of the femoral ring (Fig. 4.23 and p. 262).

The roof is formed by the lowest fibres of internal

oblique and transversus abdominis (Fig. 4.22). These

fibres arch over the canal and pass medially and downwards to form the inguinal

falx (conjoint tendon), which attaches to the crest and pectineal line of the

pubis. The anterior wall of the canal is formed by the external oblique

aponeurosis, supplemented laterally by fibres of internal oblique. These fibres

arise from the lateral part of the inguinal ligament and cover the anterior

aspect of the deep ring (Fig. 4.21). The posterior

wall is formed by the transversalis fascia, reinforced medially by the conjoint

tendon. Deep to the transversalis fascia are the inferior epigastric vessels,

which lie just medial to the deep ring (Fig. 4.23). The inferior epigastric artery may be at risk

during operations to repair inguinal hernias.

The inguinal canal is a site of potential weakness in the

abdominal wall through which intra-abdominal structures may pass, producing an

inguinal hernia (see below). However, several features of the canal’s anatomy

minimize this weakness. The obliquity of the canal ensures that the superficial

and deep inguinal rings do not overlie one another (Fig. 4.19). Furthermore,

the strongest part of the anterior wall lies in front of the deep ring and the

strongest part of the posterior wall lies behind the superficial ring. Hence,

when pressure within the abdomen rises, the anterior and posterior walls of the

canal are firmly opposed. In addition, when the abdominal muscles contract, the

canal is compressed by the descent of fibres of internal oblique and

transversus abdominis in its roof.

Contents

In the male, the canal contains the spermatic cord (Fig.

4.21). In the female, it transmits the round ligament of the uterus (Fig. 4.24), a fibromuscular cord running from the body of

the uterus to the subcutaneous tissues of the labium majus. Lymphatics from

part of the body of the uterus accompany the round ligament and terminate in

the superficial inguinal nodes (Fig. 6.11).

In both sexes, the ilioinguinal nerve (Fig. 4.14) lies

deep to the external oblique aponeurosis close to the inguinal ligament. The

nerve runs medially in the anterior wall of the canal and emerges through the

superficial ring (Figs 4.20 & 4.24).

Inguinal hernias

The inguinal canal

is the most

common site for

an abdominal hernia. Two types of

inguinal hernia are recognized. The

direct type pushes through the inguinal falx into the medial part of the canal. By contrast, the indirect (oblique)

type traverses the deep ring and turns

medially along

the canal. Hernias

of both types may

emerge through the

superficial ring and descend

into the scrotum or labium majus.

Direct and indirect hernias are distinguished by their relationships to the inferior epigastric

vessels. A direct hernia lies

on the medial

side of

these vessels, while

the indirect type enters the inguinal canal lateral to them. The

processus vaginalis normally closes but may remain patent in infancy, leaving a

tubular channel connecting with the

peritoneal cavity. Herniation

along the patent

processus, called an infantile

inguinal hernia, is more common in the male child and may extend into the

tunica vaginalis around the testis (p. 151).