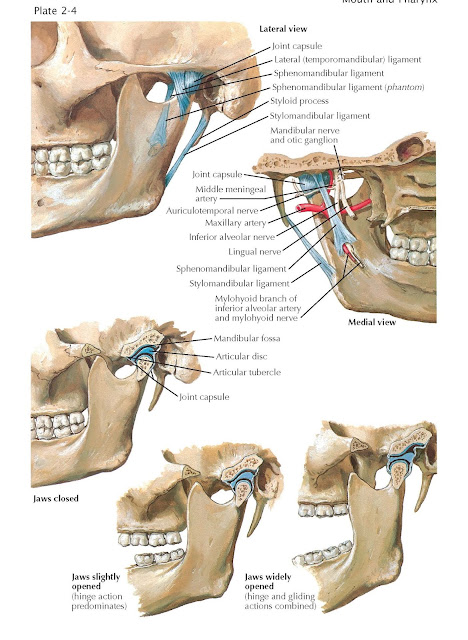

Temporomandibular Joint

The bony structures that enter into the formation of this joint are the head

of the mandibular condyle and the mandibular fossa and articular

tubercle of the temporal bone above. The head of the mandible is

ellipsoidal, with the long axis directed medially and slightly posteriorly.

This articular surface is markedly convex in the sagittal and coronal planes.

The articular surface on the temporal bone is concave posteriorly but becomes

more convex anteriorly. A fibrocartilage articular disk is inter- posed

between the two articular surfaces just described. Each surface of the disk

more or less conforms to the articular surface to which it is related, but the

shape of the disk between individuals is quite variable. The cartilage that

covers the bony articular surfaces differs from that of most joints in that it

is constituted from fibrocartilage tissue rather than hyaline cartilage,

although its gross appearance is similar to that of the articular cartilages of

other joints.

The temporomandibular joint is a true,

or synovial, joint, with two synovial spaces, one superior to the articular

disk and one inferior to it. This joint can be further described as having a hinge

motion in the lower space and a sliding motion in the upper space.

The capsular ligament is rather

loosely arranged, being attached superiorly to the margin of the articular

surface on the temporal bone and affixed inferiorly around the neck of the

mandible. The capsular ligament is firmly attached to the entire circumference

of the articular disk. Forming a pronounced thickening of the lateral aspect of

the capsule is the lateral temporomandibular ligament, which runs

inferiorly and posteriorly from the inferior border of the zygomatic process of

the temporal bone to the lateral and posterior sides of the neck of the

mandible. Two accessory ligaments are not blended with the capsule. The rather

thin sphenomandibular ligament runs from the spine of the sphenoid bone

to the lingula of the mandible, and the stylomandibular ligament, a

thickened band of deep cervical fascia, runs from the styloid process to the

lower part of the posterior border of the ramus of the mandible.

The temporomandibular joint receives

its nerve supply from the auriculotemporal and masseteric branches of

the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. Its arterial supply comes via

branches of the maxillary and superfi ial temporal arteries from the external

carotid artery.

The basic movements that are allowed

in the temporomandibular joint are (1) gliding of the articular disk anteriorly

and posteriorly on the articular surface of the temporal bone, accompanied by

the head of the mandible (which moves with the disk because the disk is

attached near the joint capsule’s attachment to the neck of the mandible and

the external pterygoid muscle is attached to both) and (2) the hinge movement

that takes place between the head of the mandible and the articu- lar disk. In

opening of the mouth, both movements are involved, with the hinge movement

predominating in slight opening and the gliding movement predominating in wide

opening. When chewing, one condyle remains more or less in position, while the

other moves backward and forward. This is combined with slight elevation and

depression of the mandible. If the mouth is opened just enough so that the

upper and lower incisor teeth can clear each other, the jaw can be protracted

and retracted, with the movement occurring in the upper joint.