Acute Coronary Syndromes: ST Segment Elevation Myocardial

Infarction

Patients usually present with sudden onset central

crushing chest pain, which may radiate down either arm (but more commonly the

left) to the jaw, back or neck. The pain lasts longer than 20 min and is not

relieved by glyceryl trinitrate (GTN). The pain is often associated with

dyspnoea, nausea, sweatiness and palpitations. Intense feelings of impending

doom (angor animi) are common. Some individuals present atypically, with

no symptoms (silent infarct, most common in diabetic patients with

diabetic neuropathy), unusual locations of the pain, syncope or pulmonary

oedema. The pulse may demonstrate a tachycardia or bradycardia. The blood

pressure is usually normal. The rest of the cardiovascular system examination

may be unremarkable, but there may be a third or fourth heart sound audible on

auscultation as well as a new and/or worsening murmur, which may be due to

papillary muscle rupture in the left heart.

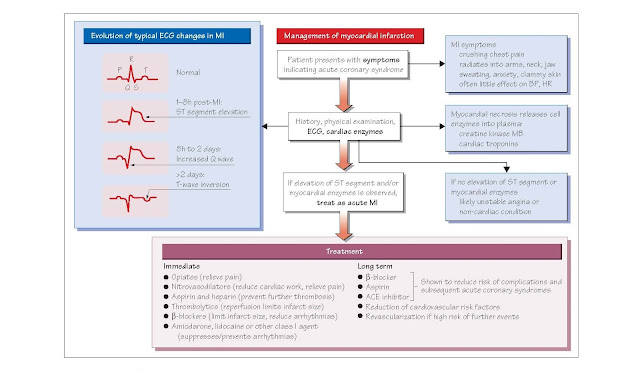

· ECG: ECG changes associated with myocardial infarction (MI) indicate the

site and thickness of the infarct. The first ECG change is peaking of the T

wave. ST segment elevation then follows rapidly in a ST elevation myocardial

infarction (STEMI).

·

Troponin I: elevated plasma concentrations of troponin I indicates that myocardial

necrosis has occurred. Troponins begin to rise within 3–12 h of the

onset of chest pain and peak at 24–48 h and then clear in about 2 weeks. It is

important that a troponin level is interpreted in the clinical context, because

conditions other than MI can damage cardiac muscle (e.g. heart failure,

myocarditis, pericarditis, pulmonary embolism or renal failure). Patients

presenting with suspected acute coronary syndromes (ACS) should have troponin

measured at presentation. If it is negative, it should be repeated 12 hours

later. If the 12 h troponin is also negative, then MI but not unstable angina

can be excluded.

Management

Immediate In the

ambulance or on first medical contact, individuals with suspected MI are

immediately given 300 mg chewable aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel to

block further platelet aggregation. Two puffs of GTN are sprayed

underneath the tongue. The patient is assessed by brief history and a clinical

examination, and a 12-lead ECG is recorded. The patient is given oxygen via a

face mask. Morphine, which has vasodilator properties, together with an

anti-emetic (e.g. metoclopramide) is administered to relieve pain and anxiety,

thus reducing the tachycardia that these cause. A β-blocker (e.g.

metoprolol) should be given unless contraindicated (e.g. LV failure or moderate

to severe asthma) because β- blockers decrease infarct size and have a positive

effect on mortality. The preferred treatment of a confirmed STEMI is revas cularization

with percutaneous coronary intervention (see Chapter 43) of the

blocked artery within 2 h of symptom onset. Ideally, every hospital would be

equipped with the ability to perform per- cutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

but in reality this is not the case. However, those that do not have the

capacity for PCI are affiliated with centres that do and protocols exist to

enable the rapid transfer of patients. If it is not possible to get the patient

to a centre for PCI in less than 2 h from symptom onset, the alternative is

pharmacological dissolution of the clot with thrombolytic agents within 12 h of

presentation unless contraindicated (see below). There are specific ECG

criteria for the diagnosis of STEMI and use of thrombolysis: ST segment

elevation of >1 mm in two or more limb leads or >2 mm in two or more

chest leads, or new onset left bundle branch block, or posterior

changes (ST depression and tall R waves in leads V1–V3). If thrombolysis

fails, the patient must be sent for rescue PCI to be performed as soon as

possible.

Subsequent Long-term

treatment with aspirin, a β-blocker and an angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitor (ACEI) reduces the com- plications of MI and the risk of

reinfarction. Cessation of smoking, control of hypertension and diabetes, and

reduction of lipids using a statin (see Chapter 36) are vital.

Thrombolysis is the

dissolution of the blood clot plugging the infarct-related coronary artery. As

described in Chapter 43, thrombolytic agents induce fibrinolysis, the

fragmentation of the fibrin strands holding the clot together. This permits reperfusion

of the ischaemic zone. Reperfusion limits infarct size and reduces the risk

of complications such as infarct expansion, arrhythmias and cardiac failure.

Clinical trials, notably ISIS-2 (1988), have demonstrated that thrombolytic

agents reduce mortality by about 25% in STEMI, although patients without ST

elevation (i.e. NSTEMI) do not benefit from thrombolysis. It is critical

that thrombolysis is instituted as quickly as possible. Although significant

reductions in mortality occur when thrombolytics are given within 12 h of

symptom onset, the greatest benefits occur when therapy is instituted within 2

h (‘time is muscle’).

The two main agents for thrombolysis are streptokinase

(SK) and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) (see Chapter 43). tPA

appears to have a slight survival benefit over SK, but the former is much less

expensive. tPA is very quickly cleared from the plasma, and reteplase and

tenecteplase are newer agents that have been made by modifying the

structure of tPA in order to impede plasma clearance. Both can therefore be

given by bolus injection by para- medics, thus facilitating prehospital

thrombolysis.

The main risk of thrombolysis is bleeding, particularly

intracerebral haemorrhage, which occurs in ∼1% of cases. Contraindications to thrombolysis therefore include

recent haemorrhagic stroke, recent surgery or trauma, and severe hypertension.

Other drugs used in acute myocardial infarction Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy is used after MI to prevent further

platelet aggregation and thrombosis. The ISIS-2 trial demonstrated a 23%

reduction in 35-day mortality in patients randomized to aspirin. Combined

aspirin and SK had an additive benefit compared with placebo (42% reduction).

Following an initial 300 mg loading dose, 75 mg/day aspirin should be given

thereafter for life to all patients to prevent vessel occlusion and infarction.

Because tPA, reteplase and tenecteplase are more fibrinspecific than SK,

intravenous heparin should be given for a duration of 48–72 h to reduce the

risk of further thrombosis when these agents are administered, or when the patient

is at high risk of developing systemic emboli (e.g. with anterior MI or atrial

fibrillation). β-Blockers are beneficial in MI for several reasons. They

diminish O2 demand by lowering heart rate and decrease ventricular

wall stress by lowering afterload. They therefore reduce ischaemia and infarct

size when given acutely. They also decrease recurrent ischaemia and free wall

rupture, and suppress arrhythmias (see Chapter 48). Long-term oral β-blockade reduces

mortality, recurrent MI and sudden death by about 25%.

ACEI (e.g. lisinopril,

ramipril) reduce afterload and ventricular wall stress and improve ejection

fraction. Inhibition of ACE raises bradykinin levels, which may improve

endothelial function and limit coronary vasospasm. ACEI also limit ventricular

remodelling and infarct expansion (see Chapter 47), thereby reducing mortality

and the incidence of congestive heart failure and recurrent MI. Therapy should

be instituted within 24 h in patients with STEMI, especially if there is

evidence of heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction, and should continue

long term if LV dysfunction remains evident.

Complications of acute myocardial infarction

There are two main groups of complications associated

with acute MI: mechanical and arrhythmic.

With large infarcts (>20–25% of the left ventricle)

depression of pump function is sufficient to cause cardiac failure. An

infarct involving more than 40% of the LV causes cardiogenic shock. Rupture of

the free LV wall is almost always fatal. Severe LV failure (cardiogenic shock)

as a result of MI is heralded by a large fall in cardiac output, pulmonary

congestion and often hypotension. The mortality is extremely high. Treatment

involves O2 to prevent hypoxaemia, diamorphine for pain and anxiety,

fluid resuscitation to optimize filling pressure and positive inotropes

(e.g. the β1-agonist dobutamine) are infused to aid myocardial

contractility. Revascularization is crucial. Intraortic balloon counterpulsation

can be used temporarily to support the circulation. A catheter-mounted

balloon is inserted via the femoral artery and positioned in the descending

thoracic aorta. The balloon is inflated during diastole, increasing the

pressure in the aortic arch and thereby improving perfusion of the coronary and

cerebral arteries. During systole, deflation of the balloon creates a suction

effect that reduces ventricular afterload and promotes systemic perfusion.

Rupture of the ventricular septum creates a ventricular

septal defect (VSD) and may result in leakage of blood between the ventricles.

Rupture of the myocardium underlying a papillary muscle, or more rarely of the

papillary muscle itself, may cause mitral regurgitation, detected

clinically as a pansystolic murmur radiating to the axilla. Dressler’s

syndrome is the triad of pericarditis, pericardial effusion and fever.

Arrhythmias in the acute

phase include ventricular ectopic beats, and the potentially life-threatening

broad complex (QRS complex >0.12 s) tachyarrhythmias, ventricular

tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF). Supraventricular arrhythmias

include atrial ectopics, atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. Bradyarrhythmias

are also common, including sinus bradycardia, and first-, second and thirddegree

AV block. Infarct expansion (see Chapter 44) is a dangerous late

complication.