Organ Allocation

There are many more people on the transplant waiting list than

there are organs available. To manage this shortage access to the waiting list

is restricted to those meeting strict eligibility rules. Once on the waiting

list allocation follows pre-defined rules to ensure fairness.

Eligibility for transplantation

Criteria vary from organ to organ, and country to country. In

addition, different considerations may be necessary for patients needing a

second transplant after the first has failed, particularly since for most

organs the results for second and subsequent trans- plants are inferior to

first transplants. For kidney, pancreas and liver there must be an expectation

that the recipient will survive 5 years after the operation. UK listing

criteria are given below.

Kidney transplantation

Already on, or estimated to be within 6 months of starting

dialysis (e.g. using a reciprocal creatinine graph). Re-transplantation is permitted providing it is surgically

feasible and the patient is fit; the main limiting factor is sensitisation

against HLA antigens.

Pancreas transplantation

1. Combined

(simultaneous) pancreas and kidney (SPK) transplantation:

GFR ≤ 20 ml/min or on dialysis and type 1 diabetes (or type 2 if BMI

<30 kg/m2).

2. Pancreas

or islet transplantation alone (PTA/ITA): life-threatening

hypoglycaemic unawareness.

3. Pancreas

after kidney transplantation (PAK): severe diabetic complications and

satisfactory function of prior renal transplant, since function is affected by

increased doses of nephrotoxic immunosuppression.

Liver transplantation

There is no bar on re-transplantation, but since results of retransplants

are so much poorer, the patient should be otherwise in good health. Individual

criteria exist for subgroups, such as hepatocellular tumours or acute liver

failure (see Chapter 33).

Heart transplantation

Patients are accepted according to internationally agreed

criteria. Many patients are now supported by mechanical devices, and are

regarded as stable on the waiting list. They only receive priority if they

develop complications such as drive-line infections. Re-trans- plants can be

done with reasonably good outcomes, but not in the first 3 months after the

initial procedure.

Lung transplantation

Most patients are now listed for bilateral lung transplants. The

only group regularly receiving single lungs are those with fibrotic disease,

where the shrunken chest cavity cannot easily accept a pair of lungs.

Re-transplants are done with increasing frequency, although still

amount to only 5–6% of activity.

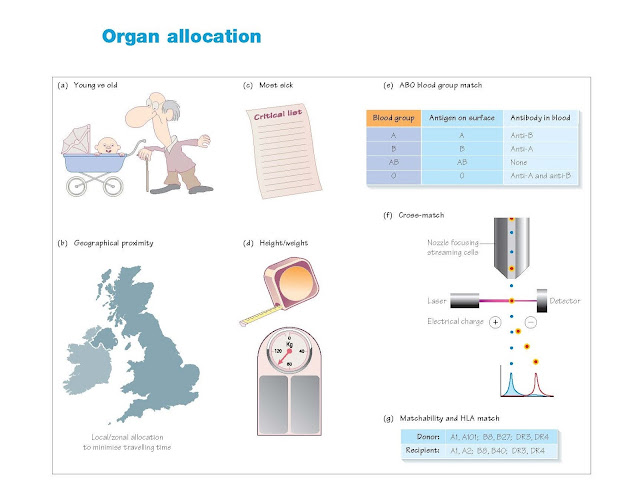

Principles in organ allocation

Organ allocation is an exercise in distributive justice, how to

fairly divide up a limited resource. There are several criteria that may be

used for organ allocation.

Equity (fairness): everyone

should have equal access to organs. Such a scheme would allocate organs first

to those who have been waiting longest, and to young and old alike.

Utility: organs should be allocated to achieve

the greatest number of life-years following transplantation, independent of

other factors. For example, since outcomes of kidney transplantation are poorer

in those already on dialysis and in the elderly, these two groups would be

excluded in a utilitarian allocation scheme, in direct contrast to the

egalitarian approach.

Greatest need: the organ goes to the person whose

medical condition demands it the most.

Greatest benefit: organs are

allocated to achieve the greatest benefit, in terms of life-years gained,

compared with remaining on the waiting list. Such allocation acknowledges that

organs are different, with young donor organs having a better anticipated longevity

than older organs. Thus an old donor kidney may be best allocated to an older

recipient, who has a high mortality on dialysis and for whom an old kidney

would increase their survival significantly. A young recipient has a better

survival on dialysis so there is less gain from having an old kidney, which

would last only a short time period.

Allocation in practice

In reality, current allocation schemes involve a mixture of the

above principles. Organs are allocated to ABO-identical recipients, with the

exception of group A organs, which may go to AB recipients, and occasional

group O organs, which may go to group B (or A or AB) recipients in special

circumstances (e.g. medical urgency or HLA sensitisation).

Organs are transplanted to avoid pre-existing donor-specific HLA

antibodies (a positive cross-match), with the exception of the liver, which can

be transplanted into a recipient who possesses antibodies to the donor’s MHC

class 1 antigens.

Kidney

Kidneys are allocated primarily to HLA-matched recipients, prioritising

sensitised patients over non-sensitised, children over

adults. Thereafter allocation is according to a complex formula

that assigns points for:

· HLA

mismatch, aiming to optimise matching

· time

on the waiting list, prioritising long waiters

· sensitisation

(HLA antibodies) and matchibility (unusual HLA type), giving priority to

patients who are hardest to find a compatible transplant

· HLA-B

and -DR homozygous recipients, correcting an imbalance that prioritising

according to HLA mismatch creates

· age

difference, aiming to minimise age difference between donor and recipient.

In addition children (under 18) get priority over adults.

Pancreas for islets or whole organ

An algorithm assigns points for:

· HLA

mismatch, aiming to optimise matching

· HLA

sensitisation and matchibility

· waiting

time, giving additional priority to an islet recipient awaiting a second graft

and a pancreas recipient on dialysis

· distance

of donor to recipient centre, to minimise ischaemic time.

Liver

Livers are allocated within seven zones in the UK corresponding to

each liver transplant unit. Priority is given to the sickest patient (UKELD

score, see Chapter 33) of a compatible size – big livers don’t fit small

abdomens.

A ‘super-urgent’ scheme exists for anyone with acute liver failure

with an expected of survival of less than 3 days; a third of these patients die

while waiting and outcomes are poorer than for chronic liver disease.

Heart

Like livers, hearts and lungs are allocated within zones corresponding

to each of the six transplant centres. Matching is done by blood group and size

of donor, which needs to be within 10% of that of the recipient. Female hearts

placed in male recipients do measurably less well, and this combination is

avoided.

There is also an urgent scheme for hearts, which accounts for

nearly half of all transplants performed. The results are at least as good as

those for ‘elective’ patients. These recipients have the most to gain from

transplantation.

Lung

Size is of great importance in lung allocation–large lungs do

not fit into small recipients. If small lungs are placed in a large chest they

become over-inflated. Allocation is done as for hearts and livers, on a local

basis, but there is no urgent system. Individual centres identify the sickest

patients on their waiting list. A lung that cannot be used locally is offered

nationally around the other centres.

Intestine

Intestinal donors are offered as a priority to the four intestinal

transplant centres (two adult, two child). For most intestinal transplants size

is the critical factor, with only the smaller donors (below 50 kg) being suitable.