FROZEN SHOULDER

The

clinical and anatomic pathology in frozen shoulder is derived from an acute

inflammatory synovitis followed by an intracapsular soft tissue fibrosis,

resulting in contracture of the capsule.

Some have made an analogy of frozen shoulder to

Dupuytren contraction in the palmar fascia of the hand. Dupuytren contracture

has been associated with myofibroblasts present within the fibrous tissues, and

these same cells can be found in the shoulder capsule with frozen shoulder.

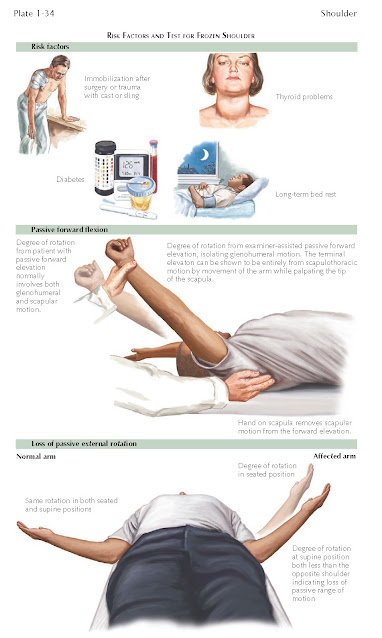

Frozen shoulder is commonly seen in association with thyroid disorders as well

as diabetes. Patients with these associated systemic diseases often have a more

severe and refractory clinical course. When associated with thyroid and

diabetic changes, the treatment of frozen shoulder is often more difficult. The

recovery phase is longer and protracted, and the recurrence rate and the number

of treatment failures are higher with both surgical and nonsurgical treatment.

There is a role for intra-articular

therapy with a corticosteroid, particularly in the treatment of early stages

of frozen shoulder in which there is acute inflammation of the synovium. As the

disease progresses through the second stage with more fibrosis and fewer

inflammatory changes, corticosteroid injections appear to have less of a

clinical effect. Nonsurgical treatment is focused on passive range of motion

stretching exercises that should take into account all portions of the capsule

and affect all arcs of motion to include forward flexion, abduction, and internal

and external rotation exercises. In many cases, the patient’s shoulder symptoms

are accompanied by significant pain, and as such the exercise program needs to

be performed gently but on a daily basis. Home-based exercise programs

instructed by a physical therapist are preferred. Stretching exercises in phase

I and phase II are shown later in discussion on rehabilitation. Home exercises

should be done daily and frequently for short periods of time. Typically, each

exercise session should include five of the types of stretches shown later in

the rehabilitation discussion each for 2 minutes, for a total of 10 minutes of

exercise at regular intervals at least five times per day. Persistence with

this regimen accompanied by good pain management will generally result in

significant improvement after 6 to 8 weeks. When pain is diminished and range

of motion near 80% of normal, a strengthening program can be added to the

overall program and the frequency of the stretching program can be diminished

and the length of time for each session increased to 15 to 20 minutes three

times each day.

In a small percentage of patients with

refractory clinical symptoms associated with significant loss of passive arcs

of motion, surgical management can be very effective. Idiopathic frozen

shoulder (adhesive capsulitis) is most responsive to both nonoperative and

surgicalmanagement as defined previously. Arthroscopic capsule release

involving all portions of the capsule is an effective mechanism to release the

contracted tissue and allow for ease of movement and postoperative

rehabilitation. Postoperative pain management should include consideration of

regional blocks. As with all types of treatment, pain management is important

and supports an effective postoperative rehabilitation program.

Examination of the frozen shoulder can

demonstrate loss of passive range of motion of the shoulder and is best tested

in the supine position as shown in Plate 1-34. As the examiner tries to further elevate the

arm, the examiner’s hand realizes loss of glenohumeral motion, and the terminal

phases of elevation are entirely related to scapular thoracic movement. In

addition, loss of passive external rotation can be seen in both the supine as

well as the seated position, as shown in Plate 1-34. Motion should be tested for both passive and

active range of motion. Loss of active range of motion in the setting of normal

passive motion is often related to weakness secondary to rotator cuff function

(see Plates 1-38, 1-40, and 1-43).