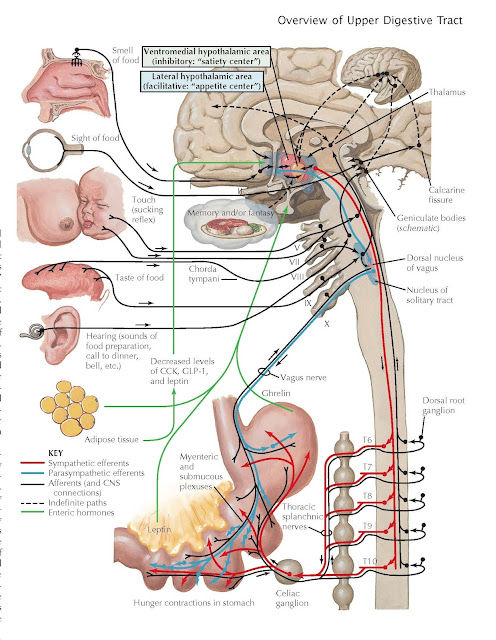

Hunger and Appetite

Food intake is due to

a complex interplay of emotional factors, learned behaviors, CNS regulation,

fat cell thermoregulatory effects, and the digestive system. It has become

increasingly clear that the intake of food is influenced by what appears to be

an adipose “set point,” which results in a relatively stable weight in most

individuals despite efforts to change their weight. The ingestion of food

occurs in response to need (hunger) or desire (appetite). Hunger describes

the complex behavioral responses evoked by depletion of body nutrient stores

required for metabolic needs. Studies by Pavlov and his colleagues in the early

1900s emphasized the importance of cortical functions and the vagus nerve

through learned behaviors and their associations with food intake. The fact

that food-seeking behavior is manifested in the unconditioned state, as in

newborn or anencephalic infants or decerebrate animals, emphasizes the

important role of lower brain functions, including the reticuloactivating

system and hypothalamus.

The digestive system has a major influence on appetite

and hunger. A common sensation described by patients as hunger is discomfort

localized to the epigastrium and perceived as emptiness, gnawing, or tension.

The fact that such ‘hunger pangs’ are experienced by individuals whose stomach

has been removed or denervated is evidence that hunger contractions are

not simply related to gastric contractions. On the other hand, it is clear that

the stomach is the major source of the hormone ghrelin, which is an

important stimulant of food intake. This 28 amino acid peptide is released from

X/A-like cells in the oxyntic glands of the gastric fundus but is also found in

the pancreas and small intestine. It is structurally related to motilin. Its

release leads to increased gastric smooth muscle contractions and stimulation

of CNS appetite centers that stimulate food intake.

Anorexia is not a common

symptom in patients with complete denervation of the small intestine, as occurs

in small bowel transplantation. On the other hand, hormones released as part of

the phenomenon known as the ileal brake have a significant influence on

appetite, including peptide YY3-36, which suppresses food intake.

Surprisingly, basal levels and postprandial levels of peptide YY are decreased

in obese patients.

A variety of other gut neuropeptides influence food

intake. Neuropeptide Y, released from the pancreas as well as the hypothalamus,

increases food intake. Insulin can also increase food intake. Cholecystokinin,

released primarily from the duodenum, reduces food intake.

In addition to influences from the CNS and digestive

system, adipose tissue also regulates appetite. The key appetite suppressant leptin

is synthesized and released from adipose tissues. Leptin is a hormone with

extraordinarily broad influences on metabolism, growth, angiogenesis, and other functions;

it appears to primarily serve as the satiety hormone. Leptin modifies

appetite primarily through its release by white adipose tissue but is also

synthesized and released by brown adipose tissue, skeletal muscles, the placenta,

ovaries, mammary epithelial cells, and bone marrow. In the digestive tract, it

is released by cells in the gastric fundus and by gastric chief cells. It acts

as an internal modulator of energy homeostasis, metabolism, and cell

replication. Although its primary effects are thought to be mediated by its

effects on the hypothalamus, especially on serotonin cells, there are leptin

receptors throughout the body on many types of cells. It is clear that leptin

release is suppressed by fasting, well before fat stores per se are altered,

and is increased by stress, insulin, and corticosteroids and, paradoxically, in

obese persons.

Fat stores, particularly of brown adipose tissue, also

influence appetite. Brown adipose tissue plays a major role in thermogenesis

and appears to be regulated by the CNS hormone orexin. It may be more

involved with energy expenditure than appetite per se. Orexin is a neuropeptide

hormone structurally related to the gut hormone secretin. It is also released

from the hypothalamus and is responsible for both arousal and appetite. It

increases lipogenesis. In addition to the hypothalamus, it is also present in

neurons throughout the CNS. Orexin release is inhibited by leptin and increased

by action of the gastric hormone ghrelin. Decreased orexin can lead to a

feeling of lowered energy which may cause a person to eat more to acquire

energy. Such reflexive food intake in the setting of reduced energy expenditure

can contribute to obesity.