Diagnostic Aids in Gastric Disorders

Every

diagnostic evaluation must begin by taking a skilled history and performing a

physical examination, but additional aids are usually necessary to make a

definitive diagnosis that will provide a specific plan for effective treatment.

Following the history and physical examination, laboratory testing and

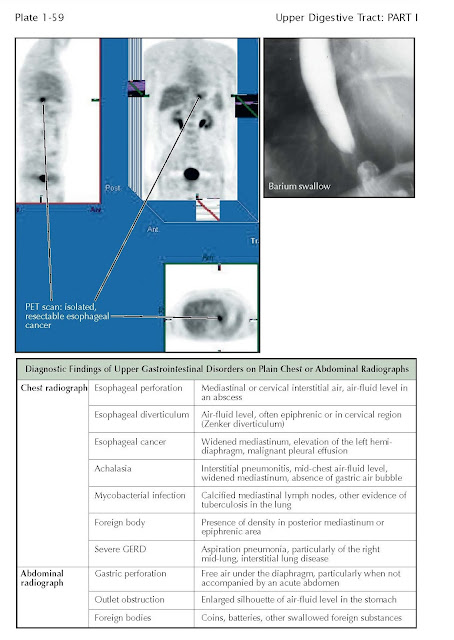

noncontrast chest or abdominal radiographs are often obtained. Common

radiographic findings on plain x-rays (no contrast agent administered) for

common upper digestive disorders are shown. The value of more precise imaging

technologies with endoscopic and radiographic studies is discussed with Plates

1-61 to 1-64 and of breath testing with Plates 1-65 and 1-66. An important

element of a thorough physical examination of a patient with symptoms of a

digestive disorder is evaluation of the stool for blood. Detecting blood from

the upper gastrointestinal tract using fecal occult blood testing with a

guaiac-based technology, while less specific, is more sensitive than fecal

immune testing for hemoglobin because the immunogenicity of a hemoglobin

molecule released in the esophagus or stomach can be degraded by pancreatic and

small intestinal digestive enzymes.

Physiologic testing of acid production and exposure and

of motility functions of the upper digestive tract is a commonly used,

invaluable tool. Three types of esophageal and gastric pH monitoring are in

common use. The traditional esophageal pH study provided only a transnasal

24-hour study of reflux. It is time honored and safe and provides accurate

information about the severity of exposure of acid in both the esophagus and

stomach. Alternatively, an intraesophageal clip pH study can be

performed by placement of a pH electrode 5 cm above the gastroesophageal

junction using endoscopy. It has several advantages over the transnasal probe

because it is wireless and therefore does not have the inconvenience,

embarrassment, potential risk, and dis- comfort of the transnasal device. It

records, for 48 hours, the intraesophageal pH measures as the patient eats and

sleeps as usual; this can be a challenge with the transnasal device. The major

disadvantage of both devices, however, is that pH recordings only report the

severity of acid reflux. A major advance over both of these techniques is high-resolution

manometry and the impedance reflux study. High-resolution manometry is

performed with a probe that has multiple recording electrodes, permitting a

more rapid and accurate evaluation of esophageal motility testing throughout

the length of the esophagus, without the annoyance of moving the device. More

importantly, the impedance technology permits the evaluation of both acid and

nonacid reflux and fluid dwell time and a correlation between manometry and

bolus transit. This device is limited by recording for only 24 hours and by placement

of the catheter transnasally, but the increased accuracy and extensive

diagnostic information provided coupled with the very small diameter of the

device make it the procedure of choice for esophageal motility and reflux

studies.

Physiologic testing of gastric motility and pH physiology

are also commonly performed. Gastric motility is most commonly evaluated after

a patient has eaten a meal of radio-labeled liquids and solids in the nuclear

medicine department of a hospital or an outpatient facility. The test

involves little radiation, is easy to perform, and has essentially no risk for

the patient. The wide variability in normal emptying rates may affect the

results, however, as may a patient’s mood and overall health, which may also

cause emptying times to vary widely (poor reproducibility). This has led to the

recommendation that recordings be made for a minimum of 4 hours and that a

standardized meal be eaten. Alter-natively, gastric motility functions can be

evaluated, along with small bowel motility, by means of a capsule motility test.

The capsule can be swallowed by a patient in the

office, and recordings are made as the patient goes about normal activities.

Gastric secretory physiology is most commonly evaluated

by a basal rate and then by a stimulated, titratable gastric secretory rate.

This test is very important in the evaluation of acid secretion in patients who

may have Zollinger-Ellison syndrome or other causes of hypergastrinemia. Gastric

acid secretory studies are described in greater detail with Plates 4-27 and 4-36.