Primary Amenorrhea

Primary amenorrhea is defined as failure to menstruate by age 16

in patients with normal secondary sexual characteristics or the failure to

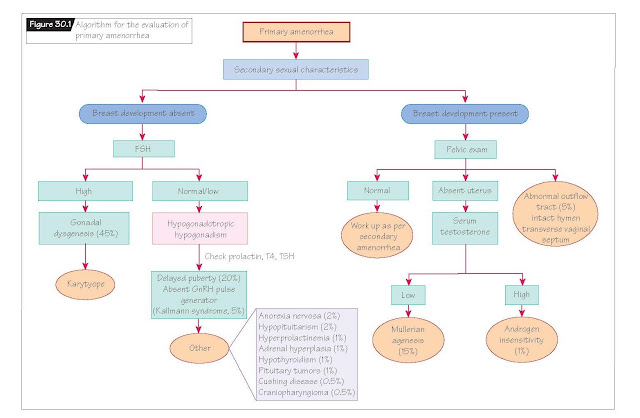

menstruate by age 14 in patients with no signs of sexual maturation (Fig.

30.1). Secondary amenorrhea is defined as the absence of three menstrual

cycles or the absence of menstrual bleeding for 6 months.

The distinction between primary and secondary amenorrhea has traditionally been emphasized because of the higher incidence of genetic and anatomic abnormalities among young women with primary amenorrhea. It remains conceptually useful to make this distinction because of several unique disorders that are found only in patients with one or the other. Still, there is much more overlap in the origins and pathophysiology of the two entities than was originally appreciated. For example, Turner syndrome is a common genetic cause of primary amenorrhea, yet some patients with Turner syndrome have sufficient ovarian reserve to undergo secondary sexual development and menarche before complete ovarian failure results in secondary amenorrhea. Other young women with chronic anovulation due to functional disorders will be classified with primary amenorrhea if the onset of the disorder occurs at puberty. In such cases, it may be more useful to assess the degree to which secondary sexual characteristics have developed in girls with absent menses. Failure of breast and pubic hair development is a sign of delayed or absent puberty and represents a specific subset of reproductive abnormalities (Chapter 29).

The distinction between primary and secondary amenorrhea has traditionally been emphasized because of the higher incidence of genetic and anatomic abnormalities among young women with primary amenorrhea. It remains conceptually useful to make this distinction because of several unique disorders that are found only in patients with one or the other. Still, there is much more overlap in the origins and pathophysiology of the two entities than was originally appreciated. For example, Turner syndrome is a common genetic cause of primary amenorrhea, yet some patients with Turner syndrome have sufficient ovarian reserve to undergo secondary sexual development and menarche before complete ovarian failure results in secondary amenorrhea. Other young women with chronic anovulation due to functional disorders will be classified with primary amenorrhea if the onset of the disorder occurs at puberty. In such cases, it may be more useful to assess the degree to which secondary sexual characteristics have developed in girls with absent menses. Failure of breast and pubic hair development is a sign of delayed or absent puberty and represents a specific subset of reproductive abnormalities (Chapter 29).

As Table 30.1 shows, causes of

amenorrhea are extensive and involve all levels of the

hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal–end-organ axis. To avoid confusion, amenorrhea

can be divided into two broad categories of abnormalities. The first and

largest category is characterized by chronic anovulation. In these patients, a

failure to generate cyclic ovarian estrogen and progesterone leads to absent or

highly irregular sloughing of an inappropriately stimulated endometrium

(Chapters 10 and 14). Chronic anovulation results from four general

pathophysiologic mechanisms: (i) the hypothalamus fails to generate a cyclic

gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) signal to the pituitary gland; (ii) the

pituitary fails to respond to appropriate signals from the hypothalamus; (iii)

the normal sex steroid feedback mechanisms fail to drive the midcycle

luteinizing hormone (LH) surge; (iv) interference with gonadal steroid feedback

by other endocrine systems. The second, much smaller, category includes

end-organ abnormalities that interfere with the ability of these organs to

respond to normal cyclic ovarian steroid production and produce visible

endometrial bleeding. Diagnosing the underlying cause of amenorrhea involves

sequential determination of the function of each of the potentially affected

compartments (uterus and vagina, ovaries, pituitary and hypothalamus).

Treatment aims to correct the underlying dysfunction so that menses resume. If

it is not possible to establish or restore menstruation, it is very important

to assess the hormonal status of untreated or inadequately treated individuals.

Chronically hypestrogenic women are at increased risk for osteoporosis (Chapter

24) and women with chronic unopposed estrogen stimulation of their endometrium

are at risk for endometrial cancer (Chapter 43). Hormonal therapy to avoid

these consequences must be considered in all

amenorrheic women.

Etiologies of primary amenorrhea

These are best understood if

categorized by: (i) the presence or absence of breast development; (ii) the

presence or absence of the cervix and uterus; and (iii) circulating

follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels. Figure 30.1 presents an algorithm

for evaluating the girl or woman with primary amenorrhea. Unsurprisingly,

abnormalities in each of the four compartments mentioned above can be

associated with primary amenorrhea.

In order of descending frequency,

the most common causes of primary amenorrhea are gonadal dysgenesis,

physiologic delay of puberty, Müllerian agenesis, transverse vaginal septum or

imperforate hymen, Kallmann syndrome, anorexia nervosa and hypopituitarism.

Complete androgen insensitivity, while much rarer than Müllerian agenesis, must

be considered in any young woman who has breasts but no uterus. All girls or

women with primary amenorrhea and an elevated FSH must have a karyotype

performed to determine whether 2X chromosomes are present or if a Y chromosome

(or even a piece of a Y chromosome) is present. The presence of any Y

chromosome genes and an intraabdominal gonad, regardless of its phenotype,

confers a risk for germ-cell tumor development. These gonads must be surgically

removed, typically at the time of diagnosis.

Gonadal dysgenesis with a

pure 45X karyotype can usually be diagnosed because of the other physical

features of Turner syndrome (Chapters 27 and 29). Other abnormalities of the

sex chromosomes can also cause amenorrhea, including 45X/46XX, other mosaics,

and 46XY with a missing SRY locus (Chapter 5). Müllerian agenesis, also

known as the Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser syndrome, is characterized by a

complete absence of the female internal genitalia, including the vagina, uterus

and fallopian tubes, in a chromosomally normal female. Its biologic cause is

unknown. Transverse vaginal septa are thought to result from failure of

the vaginal plate to resorb at the site where the Müllerian ducts fuse with it

to form the cervix (Chapters 6 and 27). Kallmann syndrome is a

developmental abnormality of the central nervous system (CNS) in which those

neurosecretory cells destined to become the GnRH pulse generator fail to

migrate from their origins in the olfactory placode to the median basal hypothalamus

(Chapter 29). In addition to reproductive abnormalities, individuals with

Kallmann syndrome also cannot smell because of the inadequate development or

complete absence of the olfactory neurons that develop from the same anlagen. Anorexia

nervosa or extreme exercise and their consequent hypothalamic suppression

can cause delayed or absent puberty if the disorder begins in childhood,

primary amenorrhea if it begins during puberty, or secondary amenorrhea if it

begins later in adolescence. Hypopituitarism most commonly results from

CNS tumors and can present as either absent or delayed puberty or amenorrhea

depending on timing of onset and the rate of tumor growth. Complete

androgen insensitivity (AI),

previously called testicular

feminization, is a rare X-linked disorder caused by mutations in the

androgen receptor that make it unresponsive to androgen. Although they can make

testosterone and other androgens, patients with complete AI cannot exhibit

androgen activity at central or peripheral target tissues. Genitalia fail to

masculinize during embryogenesis and androgens cannot exert negative feedback

on FSH production by the pituitary gland. Individuals with complete AI are

phenotypic girls and will develop breasts at puberty because the androgens

secreted by their overstimulated testes can be converted peripherally to

estrogens. They do not have a uterus. Therefore, they will not menstruate and

will present with primary amenorrhea in the presence of adequate breast development.