Growth: IV Pathophysiology

Clinical scenario

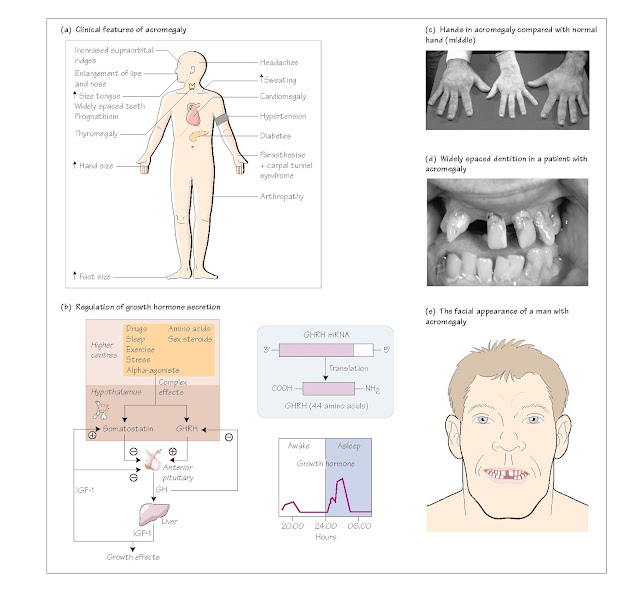

Excess growth hormone (GH) secretion causes the typical syndrome of

acromegaly. Mr SJ was a 53-year-old chef who had generally been well and rarely

went to the doctor. On this occasion he presented to his GP because of aches

and pains in the joints of his hands which were causing a problem with his

work. The GP thought he looked acromegalic and asked him a series of questions

related to his symptoms, following which he established a number of

abnormalities on examination. He referred Mr SJ to the local Endocrine Clinic

where biochemical investigations confirmed the diagnosis of acromegaly. In

particular, his plasma GH level was elevated at 25 mcg/L and failed to suppress

during a glucose tolerance test and his plasma IGF-1 concentration was five

times the upper limit of normal. An MRI scan of the pituitary revealed a

pituitary macroadenoma rising out of the pituitary fossa into the suprasellar

space but not compressing the optic chiasm. He had a good response to pituitary

surgery and subsequent radiotherapy, with resolution of many of the features of

acromegaly. The clinical features of acromegaly are shown in Fig. 12a.

Regulation of growth hormone secretion

Growth hormone (GH) secretion is regulated primarily by the hypothalamus,

which produces growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH; Fig. 12b). This action

is integrated with the action of a hormone called ghrelin, secreted

mainly by epithelial cells lining the fundus of the stomach. Ghrelin is a potent

releaser of GH from the anterior pituitary gland by binding to pituitary GH

receptors, and is also involved in energy balance (see Chapter 45).

GHRH in humans is a 44 amino acid peptide, which is released into the

portal system and binds to specific receptors on anterior pituitary

somatotrophs to stimulate GH release. The second messenger activated by GHRH is

cAMP, although the IP3 system may also be activated. The hypothalamus also produces

an inhibitory hormone called somatostatin, which inhibits GH release

from somatotrophs. Somatostatin is a 14 amino acid peptide, which also exists

in the hypothalamus in a 28 amino acid form. Both are active in inhibiting GH

secretion, which they do by inhibiting cAMP production. Both GHRH and

somatostatin have been localized to the arcuate nucleus (see Chapter 5). GH is

released in a pulsatile fashion with the major peak in secretion occurring

about one hour after the onset of sleep. In adults, circulating GH levels are

low or undetectable for most of the

day with intermittent bursts of secretion being observed. Somatostatinergic

tone is felt to be the most important determinant of production of a GH peak –

troughs in somatostatin production being associated with a GHRH peak and

subsequent GH release. The physiological feedback control of GH release is

mediated by insulin-like growth factor (IGF- 1), which stimulates somatostatin

secretion from the hypothalamus and inhibits GH secretion directly.

Pathophysiology of growth hormone secretion

GH deficiency

Causes of GH deficiency are either genetic, resulting in short stature in

children (Chapter 10) or acquired, leading to the adult GHD syndrome. GH

deficiency is treated by replacement with human growth hormone (hGH).

Originally extracted from post- mortem human pituitaries, nowadays hGH is

synthesized using recombinant DNA techniques, which obviates the hazards

inherent in using human-derived material, which carries with it the danger of infection.

GH excess

Excess secretion of GH results in acromegaly in adults (see

Clinical scenario) and gigantism in young adults if affected before

fusion of the bony epiphyses. The usual source of excess GH secretion is a

pituitary adenoma. Rarely, ectopic neuroendocrine tumours secreting GHRH occur,

either in isolation or as part of the MEN 1 syndrome (Chapter 50). Acromegaly

results in a coarsening of the facial features and of the soft tissues of the

hands (Fig. 12c) and feet. Exaggerated growth of the mandible (lower jaw)

occurs, resulting in a characteristic facial configuration (Fig. 12d and e).

There is hypertrophy of connective tissue of the kidney, heart and liver, and

the patient’s glucose tolerance is lowered by up to 50%, resulting in diabetes

in about 10% of patients with acromegaly. Other symptoms include headaches,

sweating, renal colic due to nephrolithiasis and arthralgia. A diagnosis of

acromegaly is confirmed by the failure of elevated GH levels to suppress during

an oral glucose tolerance test, coupled with elevated serum IGF-1

concentrations.

The treatment of choice for acromegaly is surgical removal of the

pituitary adenoma, plus or minus adjunctive radiotherapy or medical treatment

with somatostatin analogues or dopamine agonists. Untreated, acromegaly is

associated with increased mortality

from cardiovascular disease and cancer.