Skin Physiology : The Process Of

Keratinization

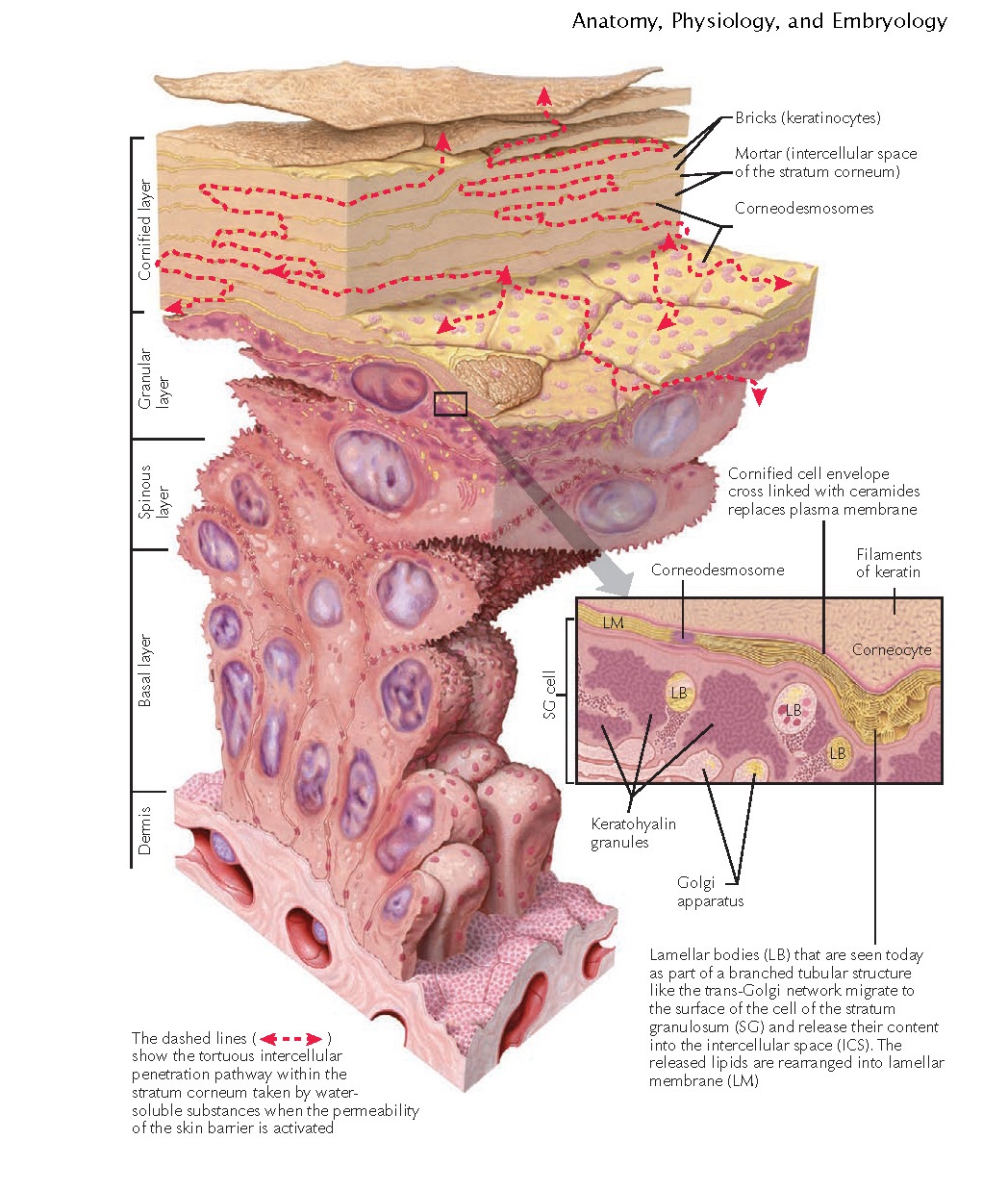

Keratinization, also known as cornification, is unique to the epithelium

of the skin. Keratinization of the human skin is of paramount importance; it

allows humans to live on dry land. The process of keratinization begins in the

basal layer of the epidermis and continues upward until full keratinization has

occurred in the stratum corneum. The function and purpose of keratinization is

to form the stratum corneum.

The stratum corneum is a highly organized layer that is relatively strong

and resistant to physical and chemical insults. This layer is critically important

in keeping out microorganisms; it is the first line of defense against

ultraviolet radiation; and it contains many enzymes that can degrade and

detoxify external chemicals. The stratum corneum is also a semipermeable

structure that selectively allows different hydrophilic and lipophilic agents

passage. However, the most obvious and most studied aspect of the stratum

corneum is its ability to protect against excessive water and electrolyte loss.

It acts as a barrier to keep chemicals out, but more importantly, it keeps

water and electrolytes inside the human body. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL)

increases as the stratum corneum is damaged or disrupted. The main lipids

responsible for protection against water loss are the ceramides and the

sphingolipids. These molecules are capable of binding many water molecules.

As keratinocytes migrate from the stratum basale and journey through the

layers of the epidermis, they undergo characteristic morphological and

biochemical changes. The keratinocytes flatten and become more compacted and

polyhedral. The resulting corneocytes become stacked, like bricks in a wall.

These corneocytes are still bonded together by desmosomes, which are now called

corneodesmosomes.

The stratum granulosum gets its name from the appearance of multiple

basophilic keratohyalin granules present within the keratinocytes. These

granules are largely composed of the protein profilaggrin. Profilaggrin is

converted into filaggrin by an intercellular endo- proteinase enzyme. Filaggrin

is so named because it is a filament-aggregating protein. Over time, filaggrin

is broken down into natural moisturizing factor (NMF) and urocanic acid. NMF is

a breakdown product of filaggrin that slows water evaporation from the

corneocytes.

The intercellular space is composed of lipids and water. The lipids are

derived from the release of the lamellar bodies (Odland bodies). Ceramides make

up the overwhelming majority of the contents of the lamellar bodies. Other

components include free fatty acids, cholesterol esters, and proteases. The

lamellar bodies fuse with the cell surface and release their contents into the

intercellular space. The fusion of the lamellar body with the cell surface is

dependent on the enzyme trans-glutaminase I.

Concurrently. the cornified cell envelope (CCE) develops. The CCE proteins

envoplakin, loricrin, periplakin, small prolinerich proteins, and involucrin

are cross-linked in various arrangements by transglutaminase I and

transglutaminase III, forming a sturdy scaffolding along the inner surface of

the keratinocyte cell membrane. As

the keratinocyte migrates upward, the cell membrane is lost, and the ceramides

that are released begin cross-linking with the CCE proteins. The cells continue

to move toward the surface of the skin and begin to lose their nucleus and

cellular organelles. The loss of these organelles is mediated by the activation

of certain proteases that can quickly degrade protein, DNA, RNA, and the nuclear

membrane.

Once the cells reach the outer layers of the stratum corneum, they begin

to be shed. On average, a keratinocyte spends 2 weeks in the stratum corneum

before being shed from the skin surface in a process called desquamation. Shedding is achieved by the

final degradation of the corneodesmosomes by proteases that destroy the

desmoglein-1 protein.

Keratinization is especially important in the diseases of cornification.

Many skin diseases have been found to involve defects in one or more proteins

that are critical in the process of cornification. Examples are lamellar

ichthyosis, which is caused by a defect in the transglutaminase I enzyme, and

Vohwinkel’s syndrome (keratoma hereditarium mutilans), which results from a

genetic mutatio in the loricrin protein and a resultant defective CCE.